|

|

|

Vol.

17, No. 3

June 2012

Human Trafficking: What Child Welfare Workers Should Know

A mother “rents” her son to a man to support a drug addiction.

A 17-year-old in foster care runs away to be with her boyfriend, who then makes her work as a prostitute.

Two children are made to work long hours in a restaurant when they should be in school.

* * * * * * * *

Most people know that because of risks to the safety and well-being of children, these scenarios would be of concern to a child welfare agency. What many do not know is that these scenarios also describe possible instances of human trafficking, a serious crime punishable under federal law by up to 20 years in prison (Federal Criminal Code,18 USC § 1584).

Child welfare professionals are often among the first to learn about child trafficking, which involves minors. By knowing how to identify and respond to victims, social workers can help bring safety and healing to children traumatized by human trafficking.

Human Trafficking

Human trafficking is a form of modern day slavery. According to the Polaris Project (2010) there are two types:

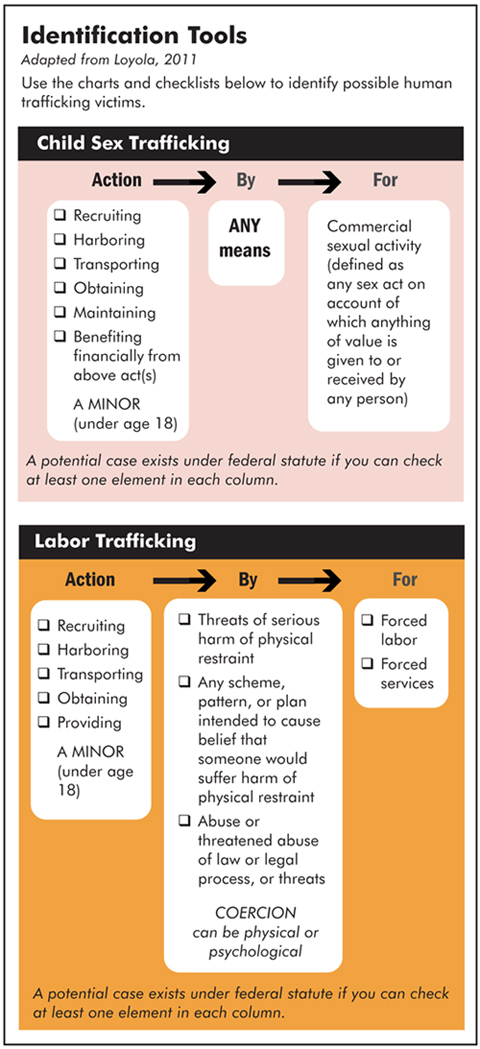

- Sex trafficking is recruiting, harboring, transporting, providing, or obtaining a person for a commercial sex act that is induced by force, fraud, or coercion. When the victim is under 18, no force, fraud, or coercion is necessary.

- Labor trafficking is recruiting, harboring, transporting, providing, or obtaining a person for labor or services, through the use of force, fraud, or coercion for the purpose of subjection to involuntary servitude, peonage, debt bondage, or slavery.

Human “trafficking” does not necessarily involve moving people from one country or place to another.

Of the victims of human trafficking, some are U.S. residents and some are non-residents. Almost all have some vulnerability that can be exploited or manipulated by the trafficker (Snyder, 2012).

Sex trafficking victims are often runaways, troubled, or homeless youth (U.S. Dept. of State, 2011). An estimated 293,000 young people in the U.S. may be at risk for being trafficked for the sex trade (Estes & Weiner, 2001).

Impact

There is overlap between child trafficking and child maltreatment. Children involved in sex trafficking are repeatedly abused by pimps, madams, and sex buyers; 95% of teens who are prostituted were victims of prior sexual abuse either by family or close acquaintances (Estes & Weiner, 2001; IOM, 2007). According to the National Human Trafficking Resource Center, the impact on victims’ well-being can be long-term and severe. Physical effects can include:

- Sleeping and eating disorders

- Sexually transmitted diseases, HIV/AIDS, pelvic pain, rectal trauma, and urinary difficulties from working in the sex industry

- Back, hearing, cardiovascular, or respiratory problems from toiling in dangerous agriculture, sweatshop, or construction conditions

Psychological effects on victims can include fear and anxiety; depression and mood changes; guilt and shame; Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD), and Traumatic Bonding with the trafficker (“Stockholm Syndrome”).

Identifying Victims

Child welfare staff have a vital role in helping identify potential child trafficking victims.

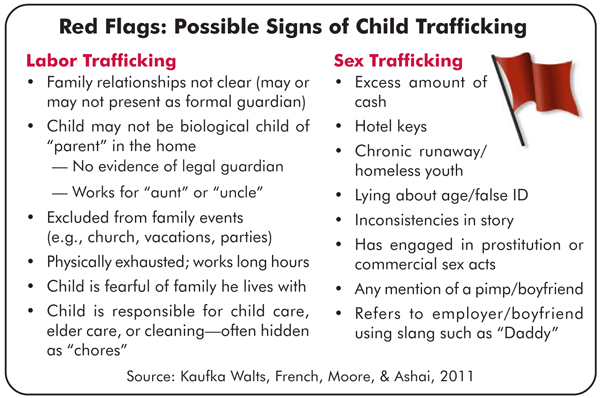

CPS Intake. Effective interviewing skills at this point in the child welfare process are key. Reporters rarely use the term “trafficking,” but by listening carefully to what a caller says, intake staff may pick up on language that could indicate possible trafficking. Be alert to references to children who are “treated like a slave,” sleep in a basement or garage, are not allowed to use the phone or leave the house, or who work too much. Any reference to prostitution, pornography, or commercial sex acts is a red flag (Loyola, 2011).

CPS Assessments. Interviewing skills are also important here. Taking time to build trust and create a safe-feeling space for victims is a priority. Use open-ended questions and mirror an interviewee’s language. Pay attention to the child’s feelings about safety. Ask, “Is it safe for you to talk with me right now? How safe do you feel right now? Are there times when you don’t feel safe? Is there anything that would help you to feel safer while we talk?” (Polaris Project, 2011)

Screening tools, such as those below, can help you identify victims. Other, more extensive screening tools are the Rapid Screening Tool for Child Trafficking and the Comprehensive Screening and Safety Tool. These are found in the Loyola University handbook profiled below.

Protecting and Supporting Victims

If you identify a potential child victim of human trafficking, respond appropriately. If it is an emergency situation, call 911. If for some reason your agency can’t respond (e.g., the report does not meet the legal mandates for CPS involvement), call the National Human Trafficking Hotline (888/373-7888).

Legal protections and services are vital to trafficking victims. Child welfare staff should work closely with law enforcement and other service providers to meet victims’ immediate needs, which may include medical attention, clothing, counseling, and safe shelter. A summary of services available to victims of trafficking can be found in the Loyola University handbook profiled below.

| A Key Resource |

|---|

| To learn more about this topic, read Building Child Welfare Response to Child Trafficking (2011) by Loyola University and the International Organization for Adolescents. This 119-page document explores in detail identification and investigations, screening tools, case management tools and resources, and much more. Available at www.luc.edu/chrc/pdfs/BCWRHandbook2011.pdf. |

In North Carolina, the Salvation Army of Wake County is part of a statewide strategy group on this issue. For more information and guidance about child welfare and human trafficking, contact their Injury Prevention Coordinator, Erica Snyder (919/886-7510; erica@uss.salvationarmy.org).

Other Learning Resources

- NC Human Trafficking Task Force Training Manual. (2008).

http://www.unc.edu/cwc/files/nchumantrafficking.pdf - Polaris Project, National Human Trafficking Resource Center,

http://www.PolarisProject.org