|

|

|

Vol.

21, No. 2

April 2016

Is Violence Against Child Welfare Workers Common?

Is violence against child welfare workers common? Although there is no single, definitive source we can turn to--there's no central agency recording violence against social workers, nor is there a commonly accepted definition of workplace violence--researchers have attempted to answer this question (Grayson, et al., 2012). The evidence we have suggests violence against child welfare workers is not at all uncommon.

Consider the work of Newhill (2003), who surveyed 1,600 social workers about violence on the job, with violence defined as physical assault, attempted assault, property damage, or threats. Newhill's analysis led her to conclude that client violence is definitely not rare: 58% of the 1,129 respondents said they had experienced at least one violent incident in their career.

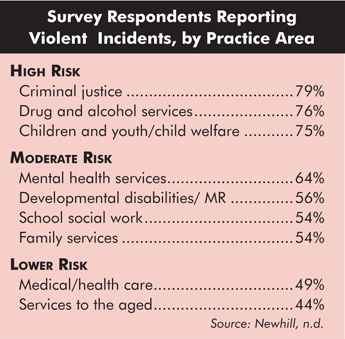

Newhill also found her respondents' risk of violence varied based on where they worked. As the figure below shows, although social workers from all areas of practice reported violence, in certain areas--including child welfare--client violence was far more common.

Another, larger study conducted in 2004 by the National Association of Social Workers (NASW) reached similar conclusions. Of the 10,000 licensed social workers surveyed, 44% reported facing personal safety issues on the job. Many who faced safety issues were less experienced (in their first five years) and worked in child welfare or mental health (Whitaker, Weismiller, & Clark, 2006).

A number of other studies found similar levels of client violence--with at least half of social workers having experienced client violence in some form (Ringstad, 2005; American Federation of State, County, and Municipal Employees, 2011).

Men More at Risk?

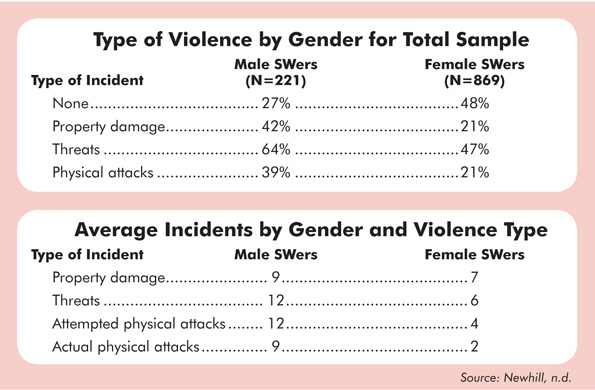

As the table below shows, Newhill (2003) found that gender seems to influence one's likelihood of experiencing violence. Across all practice areas, the male social workers participating in her study were much more likely than women to report violence and to report more violent incidents. Other studies have reached similar conclusions (Spencer & Munch, 2003; Ennis & Douglas, 2007).

What explains this finding? In an online interview Newhill noted that more male social workers work in the highest risk settings (i.e., criminal justice, drug and alcohol services, and child welfare). She added, however, "many of the male respondents told me that they were more likely to be assigned violent/aggressive clients than their female counterparts, and when a client did become violent or aggressive they were often called in to deal with the situation. So I think what's happening is that agencies are using male social workers as a kind of informal 'security force.' But the disturbing thing is that the male social workers reported they weren't being given additional training, nor were they given 'hazard pay' for taking on this additional risk. . . . That's a finding we as professional social workers and agencies need to think about...is this really just?" (Singer, 2008).

If this quote from Newhill resonates with you when you think about how things are done in your agency, we encourage you to begin a conversation about safety and the role of male social workers.

Impact on Social Workers

Experiencing client violence exacts a significant emotional toll on social workers. In Newhill's study, social workers' emotional reactions varied according to the type of incident they experienced. For example, when violence took the form of property damage, workers tended to be angry. The response to threats was often fear and anxiety. Physical attacks evoked fear, anxiety, and anger, but workers also felt shocked and shook up, helpless and inadequate, and physically exhausted. Newhill noted that physical attacks provoked trauma reactions such as sleeplessness, intrusive thoughts, and self-blame (Singer, 2008).

Given the potentially harmful impact of client violence, child welfare agencies must do all they can to prevent it and to create an environment of support that will allow staff to heal and rebound when it occurs. The training described in the next article and the suggestions in other parts of this issue may prove helpful in this effort.