|

|

|

Vol.

23, No. 1

May 2018

NC's Foster Care 18-21 Program: Benefits and Lessons Learned

North Carolina launched Foster Care 18-21 in January 2017. This program is an exciting leap forward, because it strengthens our ability to support young adults as they transition from foster care to independent adulthood.

Many people struggle with this transition, not just those in foster care. If you doubt this, consider: in 2016, one in three Americans ages 25-29 lived with their parents or grandparents--the highest in 75 years (Kopf, 2018).

Though welcome, the Foster Care 18-21 program is also a big shift. As this article explains, it brings with it not only benefits for young people, but learning opportunities for child welfare workers and their agencies.

The Program

Thanks to the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act of 2008, states can now claim federal reimbursement for foster care maintenance payments made on behalf of Title IV-E-eligible youth until they reach age 21. At least half of all states have extended care past age 18 (USDHHS, 2017).

North Carolina does this using Foster Care 18-21. Youth can enter this program by signing a Voluntary Placement Agreement (VPA). Program services and benefits include Medicaid coverage, educational grants/scholarships for attending a NC public community college or university, and:

Ongoing Case Work that includes a Transitional Living Plan, which is created and reviewed at quarterly case review meetings with the young adult's Transition Support Team; monthly contact between the young adult and social worker; quarterly home assessments (unless the young adult lives in a dorm); and assistance obtaining annual credit checks.

Placement in a home approved by the county child welfare agency. The placement does not have to be a licensed foster home. It can be in a college/university dormitory, or an approved semi-supervised housing arrangement with a roommate or a relative with the county providing supervision and oversight to the young adult. The only living situations that make young adults ineligible for the program are being incarcerated or living with the person DSS removed them from.

Foster care payments at the standard rate (currently $634/month). These are for food, shelter, clothing, personal incidentals, and ordinary and necessary school and transportation expenses. Payments may be made to a foster parent, placement agency, relative, or host family. The county may even make the payments directly to the young adult if (1) it determines this is in the young adult's best interests, (2) financial management is a goal on the Transitional Living Plan, and (3) the county works closely with the young adult on budgeting.

Program participants can also continue to access services from LINKS.

Entering & Exiting the Program

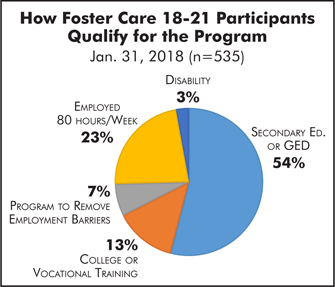

Youth who turn 18 while in DSS custody must meet one of the criteria shown in the figure below to enroll. Once enrolled, young adults must maintain their eligibility by meeting at least one of the eligibility criteria.

Participants graduate the program when they turn 21. Young adults can also leave the program at any time. As long as they are eligible, those who leave can rejoin it at any time. However, young adults can be terminated from the program if they violate their agreement with the county or are not engaging in the required meetings or are not making progress on the Transitional Living Plan. Counties must seek court review prior to terminating program services.

If they become ineligible, young adults have 60 days to become eligible again, as long as they actively seek to renew their eligibility. Otherwise, DSS will seek termination for break in eligibility.

For further details about eligibility and other aspects of the program, please refer to North Carolina policy (https://bit.ly/2qEdB4a).

Benefits

We do not yet have research findings specific to NC's Foster Care 18-21 program. However, studies from other parts of the country show that youth who remain in care past 18 are much more likely than their peers who exit foster care to have a positive housing, employment, and education status (Netzel & Tardanico, 2014).

In California, one of the first states to implement extended foster care, researchers interviewed 611 youth in care at age 16-17 and again at age 19. The vast majority felt extended care supported them in their life goals and most felt positively about the assistance they received.

This same study found that remaining in care was associated with a wide range of positive outcomes. "Young people still in care were more likely than those who had left care to be enrolled in school, reported having more social support, and had received more supportive services. They were less likely than those who had left care to experience economic hardships, food insecurity, homelessness, psychiatric hospitalization, and criminal justice system involvement."

Though these findings should be regarded with some caution since they do not take into account preexisting differences between youth who remained in care and those who left, they nevertheless provide emerging evidence of the potential benefits of extended foster care (Courtney, et al., 2016a).

Agency Lessons Learned

Despite the benefits, extending foster care to age 21 is a shift that has required some learning on agencies' part. As noted by Erin Baluyot, coordinator of the Foster Care 18-21 program for the NC Division of Social Services, providing care and supervision to adults is different.

"With minors, it's not unusual for workers to have a 'safety' mindset, with lots of focus on protocol and structure," Baluyot says. "But we want young adults to be successful and independent, so we need to let go of the reins a little bit."

Youth don't have to be in this program. For this reason, Baluyot advises workers to focus more on connection, support, and independent living. "We'd rather be involved in their lives with a less than perfect living arrangement, than not involved at all."

Thus, when assessing a living arrangement for the program, the threshold of acceptability is much lower than for a minor in care. Baluyot suggests we should be looking at the bare minimum of appropriateness--running water, functional bathroom, a place to prepare meals, a bed and place to store belongings. We want to maximize the young adult's autonomy to choose where and with whom to live. Avoid asking roommates for SSNs to run background checks, as this may compromise the young adult being able to live there.

Counties have also passed on advice to Baluyot concerning the following:

1. Finding placements. If youth have a hard time finding a living arrangement, Kelly Davis, LINKS Coordinator in Johnston County, suggests reaching out to churches or community organizations known to host exchange students.

2. Out-of-state placements. Young adults can choose to live out of state. Unfortunately, many states do not provide services for youth 18 years and older through ICPC. To overcome this hurdle, be creative in how you provide support and assess safety. As always, good communication is key.

3. Volunteering does make young adults eligible for the program. However, some counties are struggling to have this recognized by the courts, since this differs from CARS requirements. Partnering with your agency attorney to educate judges about this program is one possible solution to this barrier.

4. Revolving door. Most young adults can move back in with their parents if a job, college, or relationship does not work out. This program attempts to create a similar safety net by giving young adults in foster care the ability to re-enroll in the program as many times as needed. However, some young adults have bounced in and out of the program frequently. If you encounter this, work with the Transition Support Team to better engage the young adult.

5. Look for positive signs. Johnston County's Kelly Davis says she has seen young adults stretching themselves in exciting ways. For instance, there's been "healthy competition" between youth to see who can save enough to buy a car first. Exits and returns to the program are often a sign the program is working as intended. In the California study mentioned above, one in five of youth interviewed had left care but had chosen to return by age 19 (Courtney, et al., 2016a).

6. Truly involve young adults. This program extends support for just a few years. Make the most of this time by genuinely engaging young adults. As one put it, "Listening to professionals talk about your life and your future is like being hungry and not being allowed to decide whether or not to eat." If we really want to prepare young adults for the future, we owe it to them to treat them as partners.