|

|

|

©

2006 Jordan Institute

for Families

Vol.

11, No. 2

February 2006

American Indians in North Carolina

Building your knowledge of the different groups you serve is essential to culturally competent child welfare practice. When it comes to working with American Indians, however, it is a matter of learning not about one culture, but many. This article will help you develop some knowledge of Native Americans in North Carolina.

Nationally

According to the U.S. Census, in 2000 approximately 4.1 million people, or 1.5% of the total population, described themselves as fully or partly American Indian/Alaska Native. Of these, 2.5 million, or 0.9% of the U.S. population, described themselves Indian only. These Native peoples belonged to more than 800 tribes (NICWA, 2005).

Diversity. The number and diversity of Native tribes—and the fact that Indians are much more likely to identify themselves as belonging to one or more additional racial groups—underscores how important it is that child welfare workers approach every Indian family with respect and without making assumptions about the family’s values, culture, or approach to life (NCHS, 2005).

Sovereignty. Most Indian tribes are independent sovereign nations with a special relationship to the U.S. government. Currently there are 562 federally-recognized tribes, each of which retains the powers of self-government. Child welfare matters regarding children who are or who are eligible to be members of these tribes are governed by federal law (to learn more see this issue's article on ICWA). For a list of federally-recognized tribes dated spring/summer 2005 go to <www.doi.gov/leaders.pdf>.

North Carolina

According to the US Census Bureau, 99,551 North Carolinians, or 1% of the people in the state, described their race as American Indian during the 2000 Census. Nationally, along with Kansas, Minnesota, and Oregon, our state is ranked 12th in the percentage of its population that is Native American (US Census, 2005).

Age. As a group, North Carolina’s Indian population is younger than the state’s general population. Approximately 33% of Native Americans in North Carolina are under age 19, compared with a state average of 24% (NICWA, 2005; US Census, 2005). This means that our state’s Native population has a greater need for all types of community services for children and youth.

Distribution. Nationally, at least 50% of Native Americans live in metropolitan areas (Bennett, 2003). In North Carolina all counties have some Indian residents. Based on Census data, eight counties (Cumberland, Hoke, Jackson, Mecklenburg, Robeson, Scotland, Swain, and Wake) are home to 2,000 or more Native Americans. In several of these Indians make up a significant percentage of the population: Hoke (10%), Jackson (10%), Robeson (33%), and Swain (25%).

Affiliation. There are Native Americans from many tribes across the nation living in North Carolina. However, most belong to one of 12 North Carolina-based tribes and organizations (see below). The Eastern Band of the Cherokee is the only federally-recognized tribe based in North Carolina.

| North Carolina’s State-Recognized American Indian Tribes and Organizations |

|---|

|

According to the 2000 Census, the largest single Indian group in North Carolina is the Lumbee, who number 46,896 and make up 47% of the Native population in the state. For links to all tribal governments and Indian groups in North Carolina, including contact information, go to <www.doa.state.nc.us/cia/tribes.pdf> (dated Feb. 2005).

Contemporary Indian Family Life

Families. Forty-eight percent of American Indians are married (ICCTC, 2005). In most Indian communities, “family” is defined broadly, and often includes extended family, and even non-blood relatives. Families are often close-knit, and usually consist of groups of siblings or cousins living close together; elders may live with their adult children. Parents, aunts, uncles, and grandparents often share the responsibility for all the children in the

extended family group. Just as tribes vary markedly in culture, so do individuals and families. Red Horse and colleagues (1978) describe three common lifestyles of Indian families today:

- Traditional. Families use the tribal language and practice the tribal religion. They may participate in the dominant culture’s activities, but tribal activities take precedence.

- Bi-cultural. Persons in these families cope comfortably in both tribal and non-tribal settings. English is the predominant language. Non-Indian beliefs and recreational and social activities may be predominant. Bicultural families remain interested in Indian cultural activities.

- Pan-traditional. Conversation within the family may be in English or the native tongue. Religious beliefs may be a composite of a number of traditional forms. These families often reject activities of the dominant society in an effort to recapture traditional ways in danger of being lost or abandoned (e.g., traditional singing and dancing).

Spirituality. It has only been legal for Indians to publicly display their religious practices since the American Indian Religious Freedom Act of 1978. Therefore, many Indians are very protective of their spiritual practices.

Though Indian spiritual traditions are quite diverse, most emphasize a respect for life, a connectedness with nature, and a belief in a spiritual existence after the physical body has died. Most Indian religions promote the notion there must be balance between one’s physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health (AIMHAC, 2004).

Many Indians reject traditional Native spiritual practices and embrace Christianity; some have no strong spiritual beliefs (AIMHAC, 2004).

Child-rearing. Traditionally, responsibility for caring for, teaching, disciplining, and raising children in most American Indian cultures was shared between the child’s mother and father and other members of the tribe, especially extended family members. Many Indian families today still raise their children this way, although the increasing urbanization of Native peoples can undermine strategies connected with this approach to child-rearing.

Indian Child Well-Being in North Carolina

How are our state’s American Indian children faring? In a word, things could be better.

Willeto (2002) assessed the well-being of Native children nationally and in 13 states, one of which was North Carolina. She found that we did not compare well with other states in several important categories, including:

- Low birthweight: in 1999, 11.2% of NC’s Native American babies were born with low birthweights, compared to the national Indian average of 7.1%

- Teen birth rate: in 1999, for every 1,000 Native teen girls in NC an average of 53.5 gave birth, compared to the national Indian average of 41.4 per 1,000

- Infant mortality: between 1997-1999, NC averaged 13.7 Indian infant deaths for every 1,000 births, compared to the national Indian average of 9.1 per 1,000

- High school drop out: in 1999, 24% of North Carolina Indians dropped out of high school, compared with the national Native American average of 15.85%

We did perform better than most of the other 13 states in some areas, including child poverty: 25.4% of NC’s Indian children lived below the poverty level in 1999, compared with the national Indian average of 31.6%. Still, the fact that one in four children lived in poverty is not good.

Native Well-Being Nationally

In fact, focusing on the well-being of North Carolina’s Indian children relative to Native children in other states obscures the fact that at the national level,

Native American children and youth performed worse on nine of the ten well-being indicators Willeto measured.

The bottom line is, regardless of where they live many American Indians—adults and children—are at risk. Some of the risks they face include:

Poverty. Despite income from casinos and other projects, most Indians are worse off economically than the general U.S. population. In 2001–03, more than one in five Native Americans lived in poverty (NCHS, 2005).

Untimely Death. Native people have a life expectancy of 65 years, well below the U.S. average of 77.6 years (Bennett, 2003). In 2002 the death rate for motor vehicle-related injury for American Indian males aged 15–24 was almost 40% higher and the suicide rate was almost 60% higher than the rates for those causes for young White males (NCHS, 2005).

Violent Crime and Domestic Violence. Rates of violent victimization for both males and females are higher among American Indians than for all races. Native women are at special risk for intimate partner violence (CDC, 2005). Violence is reported in 16% of all marital relationships among Indians, with severe violence reported in 7% of these relationships. Indian victims of intimate violence are more likely than others to be injured and need medical attention (NIH, 2002).

Illness. Some illnesses, including diabetes, chronic liver disease, and cirrhosis, pose a special challenge to Native populations (NCHS, 2005). The fight against illness is made more difficult by the fact that many Indian communities have inadequate numbers of physical and mental health care providers (Cross, 2005).

Child Maltreatment. Indian children consistently have the highest rates of maltreatment victimization in the U.S. In 2002 Indian children were abused and neglected at a rate of 21.7 per 1,000 Native children; the rate for White children was 10.7 per 1,000 (USDHHS, 2005). Neglect is the most common form of maltreatment among Native Americans, while sexual and physical abuse appear to be less common than among other groups (ICCTC, 2005).

American Indian Strengths

Although the challenges they face are real, Native Americans also possess many strengths.

Foremost among these is their resiliency. Indeed, after centuries of racism, discrimination, boarding school placements, forced relocation, attempted genocide, and transracial adoption, Native Americans’ very existence is a remarkable achievement (Goodluck, 2002).

But Indians have done more than survive. Evidence for this can be found in statistics about home ownership (nearly 55% of all Native people own their own home) and education (75% of Indians age 25 and over have at least a high school diploma, 14% have at least a bachelor’s degree), and in the fact that today American Indians are growing and continuing as unique cultures and tribes.

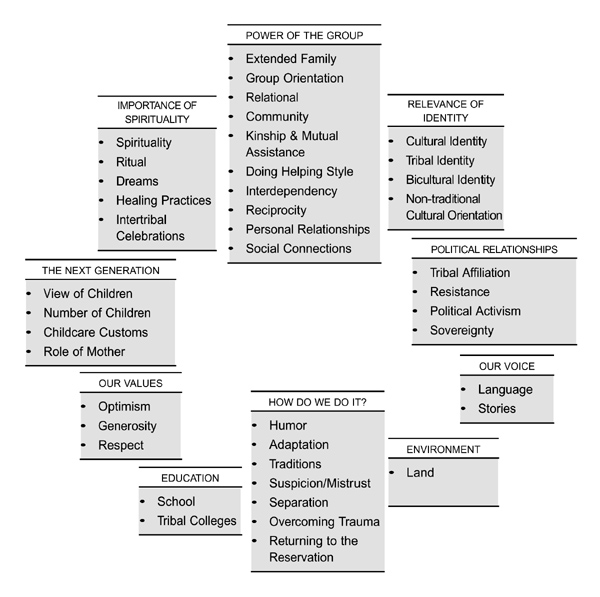

To better understand American Indians’ successes, Goodluck (2002) conducted a study in which she identified 42 Native strengths. These strengths included the sovereignty of tribes, humor, traditions, and many more:

Themes of Native American Strengths

Source: Goodluck, 2002

This list is important because it can help non-Native child welfare practitioners understand what is important to Indian individuals, families, and tribes.

Goodluck also developed a model of Native American well-being. At the heart of this model are three domains: extended family, spirituality, and social connections. Goodluck believes activities in these domains reinforce one another to create a cycle of Native American well-being.

Workers who want to improve their ability to recognize Indian strengths and empower Native families should consider reading Goodluck’s report, which contains suggestions for identifying behaviors associated with different Native strengths. It is available at <www.casey.org/Resources/Publications/NICWAWellBeingIndicators.htm>.