|

|

|

©

2006 Jordan Institute

for Families

Vol.

11, No. 4

September 2006

How Well Does NC Meet the Educational Needs of Kids in Care?

How do we fare when it comes to meeting the educational needs of children in foster care? Before we can answer this question we must consider some key information.

Key Facts about Kids in Care in NC

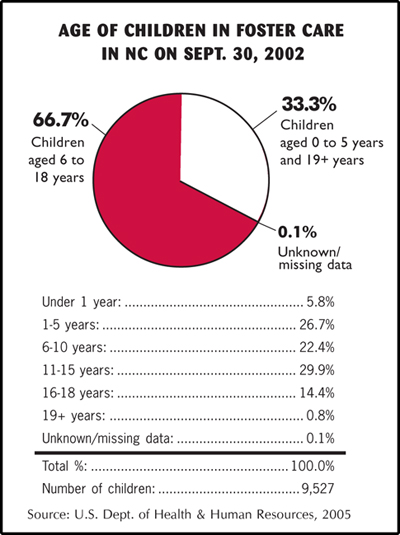

Most are in school. According to the U.S. Department of Health and Human Resources (2005), approximately two of every three children in foster care in our state on Sept. 30, 2002 were school-aged. The box below provides more detailed information.

Most are in care longer than one school year. On Sept. 30, 2002 the median length of stay in foster care for children in North Carolina was 14 months. Although this average compares favorably with length of stay in out-of-home placement in many other states, most children in foster care in North Carolina are still in care for more than one academic year. This means that even if there are no placement-related school transfers, child welfare workers, foster parents, and others advocating on behalf of the child still need to help the child negotiate the move from one teacher or grade to another.

Many face multiple placements. In 2002, 42.3% of children in foster care in our state had 3 or more placements. Many experts believe that multiple placements hurt children’s academic progress in at least two ways: (1) by causing stress and disruption in the child’s home life, and (2) by requiring transfers from one school to another, often in the middle of the school year.

Measures of Our Performance

Federal Child and Family Services Review. In 2001 federal reviewers found our state was “not in substantial conformity” with federal performance standards when it came to meeting the educational needs of foster children. In particular, reviewers were concerned that:

- Foster parents were often more involved and knowledgeable about children’s educational needs than were child welfare workers

- Information sharing with schools was sometimes poor

- There was inconsistent screening for educational needs and communication with schools for in-home cases

Federal reviewers were also concerned because only about half of the teenagers eligible for Independent Living services—some of which are educational in nature—were actually offered or received these services.

Since 2001 North Carolina has acted to rectify its performance in the area of education and other areas that were in nonconformity on the federal review. For example, it adopted the use of structured decision making tools, modified its approach to Independent Living services by creating the LINKS program, and launched the Multiple Response System (MRS) reform effort. These activities improved our performance and satisfied federal reviewers: our state exited federal Program Improvement status in June 2005.

County-Level Reviews. Individual county departments of social services also seem to be doing a good job around education. According to a report by the NC Division of Social Services, 94% of the 81 counties reviewed between December 2003 and June 2005 successfully ensured that children involved with the child welfare system received appropriate services to meet their educational needs (NCDSS, 2005).

Conclusions

Based on the information considered here, two conclusions seem warranted. First, it seems fair to say that since 2001 North Carolina’s child welfare system has made some improvement in its ability to meet the educational needs of children.

Second, given what we know about length of stay, placement stability, and the extent to which many children in foster care struggle in school, there is no room for complacency.