|

|

|

©

2007 Jordan Institute

for Families

Vol.

13, No. 1

December 2007

North Carolina's CFTs: What the Research Says

Child and family team meetings represent a significant shift in the way the child welfare system approaches families. Traditionally, child protection agencies and the courts have taken a power and control approach, mandating compliance with agency-generated treatment plans and telling families what is required of them if they wish to continue parenting their children or have their children returned home. Although motivated by a desire to ensure child safety, this approach often seems to families like coercion and threats, which can have a negative impact on families’ cooperation.

The CFT process allows families to develop their own plan for the children, empowering parents and extended family to make their own decisions and to tap into resources and community supports to assist the child. Instead of disempowering and disenfranchising families, the CFT process is designed to strengthen and sustain the family (Chandler & Giovannucci, 2004).

To many child welfare workers and administrators this seems like a change in the right direction, for the right reasons. But as professionals we cannot embrace new practices simply because they sound good. Given our goals and our system’s increasing emphasis on outcomes, we owe it to ourselves and the families and children we serve to understand what the research says about the effectiveness of new practices and approaches. Whenever possible our practice must be based on evidence.

So what does the research say about child and family team meetings as the practice exists in North Carolina? On one hand, not much—there have been few studies of the particular model of child and family team meetings used in our child welfare agencies. At the same time, there has been a fair amount of research conducted on the most well-known family-centered meeting model, family group decision making, which is also called family group conferencing.

Family Group Decision Making

Here’s what the research says about family group decision making.

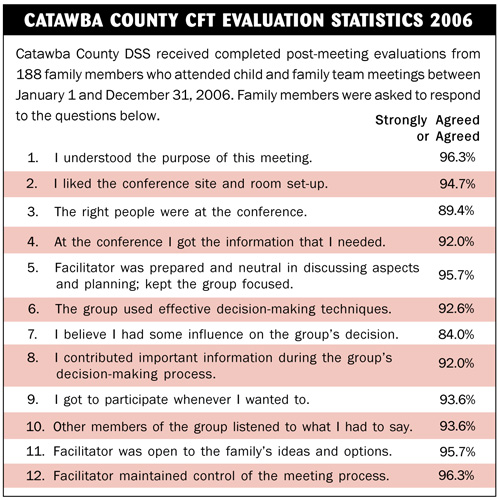

Families Like It. Participating families report that they feel respected by the process and have greater involvement and influence in decisions (Merkel-Holguin et al. 2007; FCI 2002). In a number of evaluations, families reported that they received more support from both extended family and professionals, and that they believed the children’s safety and well-being was higher as a result of the family conferencing (Mandell et al. 2001; Rasmussen 2007; Sibison 2000). Parents in a Texas program also felt more confident in their ability to help their children grow and develop (DFPS 2005). The figure below illustrates family satisfaction with child and family team meetings in one North Carolina county in 2006.

Workers Like It. Social workers report similarly positive results from using family conferencing. Specifically, professionals repeatedly cite reduced conflict with families, better collaboration after meetings, and better plans for the children than with traditional practice (DFPS 2005; FCI 2002; Merkel-Holguin et al. 2007).

Meetings Produce Acceptable, Workable Plans. On average, child welfare workers accept the plans suggested by families 95% of the time. Very few family conferences result in no plan being developed. Families appear to attend and participate in these conferences more than other forms of decision-making meetings (Merkel-Holguin et al. 2007).

Evidence about the Impact on Outcomes Is Not Yet Conclusive. Some research calls into question whether family conferencing creates lasting improvement for families. Some studies have been unable to show any clear impact on child welfare outcomes (Crampton 2007; TDFPS 2005).

In addition, at least two studies have shown that children involved in family group conferencing actually had an increase in re-referrals to child protection services compared to traditional child protection investigations (FCI 2002; Sundell & Vinnerljung 2004). There are caveats to this finding, however. Sundell & Vinnerljung found that, once they controlled for other variables, family group conferencing had a very small (0-7%) impact on this outcome.

The study of the other program, in Santa Clara, CA, suggested two possible explanations. First, the children involved in the project were more likely to have experienced neglect than other types of maltreatment, and “recurrence of maltreatment is known to occur more frequently in cases of neglect when compared to both physical abuse and sexual abuse” (p. 7). Second, the researchers surmised that there may have been a “surveillance effect” at work: as a result of the family conference process, scrutiny of these children may have been greater than for children involved in traditional child welfare.

Evidence about the Impact on Outcomes Is Promising. Still other studies suggest that family conferencing meetings may support some of the most important outcomes for children. Reported results include:

- Reductions in re-abuse rates (Merkel-Holguin et al. 2007)

- Increases in kinship placements that are as stable or more stable than traditional samples (Merkel-Holguin et al. 2007)

- Success in maintaining children’s connections with their siblings, parents, and relatives (Merkel-Holguin 2003)

- Safety of children (Gunderson, Cahn, & Wirth 2003) and mothers (Pennel & Buford 2000) involved with family conferencing

- Family conferences do not significantly increase costs (Pennell & Anderson 2005)

Family conferencing shows promise for addressing some of the other recent goals set for the child welfare system by North Carolina and the federal government. For example, various studies of family group conferencing have shown a high level of involvement by fathers and paternal relatives (Merkel-Holguin et al. 2007). In addition, a program in Michigan linked its use of meetings over a three-year period to a 20% reduction in the number of minority children in foster care (AHA 2007). And a number of states have begun using collaborative family meetings in an effort to more quickly achieve permanency for children (CWIG 2005).

Implications

There is a strong resemblance between family group conferencing and the CFTs conducted in North Carolina. Both approaches share family-centered philosophical ideas, methods, and goals. In both, the meeting is about extended family and community supports coming together to help the family create a plan for the child that builds on their strengths and addresses their needs (NCSOC 2007).

But there are important differences between the two models. For example, unlike family group conferencing, our CFT model does not insist on the use of neutral facilitators for all family meetings, nor is “family alone time” required—though it is allowed and encouraged. Unlike family group conferencing, our model encourages the use of CFTs with virtually all families receiving involuntary child welfare services at many points throughout the life of a family’s case.

Because of the similarities of these two models, we believe that existing research on family group decision making does shed some light on the effectiveness of CFTs in North Carolina. For example, it is probably safe to say that in general NC’s CFT meetings, like family group conferences, help agencies engage families and build positive working relationships. This is supported by qualitative findings from the most recent evaluation of our state’s Multiple Response System (Duke 2006).

At the same time, research conclusions about one meeting model do not automatically apply to another. We must wait for further studies of the specific approach we are using here in North Carolina before we can know for sure which families can benefit from it most, what professionals can do to accomplish the most success, and which child outcomes it improves.

In the meantime, North Carolina’s child welfare practitioners and their agencies will continue to use this promising practice in an effort to ensure the safety, permanence, and well-being of children and their families.