|

|

|

©

2010 Jordan Institute

for Families

Vol.

15, No. 2

May 2010

Meeting Children's Needs with the Medical Home Approach

Health Concerns of Children in Foster Care |

Sources cited in Sanchez, Gomez, & Davis, 2010 |

Child welfare professionals are naturally concerned about the well-being of the children they encounter. Many of these children already have or are at risk for special needs which can negatively affect them in a number of ways. Physical health issues left unidentified and untreated in childhood can have serious implications for functioning in adulthood (Sanchez, Gomez, & Davis, 2010). Unmet mental health needs, too, can lead to serious consequences later in their lives, including homelessness and incarceration (Kerker & Dore, 2006).

Fortunately, by learning about and actively supporting the medical home approach, you can help improve the quality of health and mental health care services that families and children receive while they are involved with child welfare services, and afterwards.

The Medical Home

A medical home is a partnership between the family and the family’s primary health care provider. Through this partnership, the medical home provides a single point of entry to a system of care that facilitates access to medical and nonmedical services.

In a medical home, a physician leads a team which delivers and directs care that is comprehensive (sick and preventive/well care), compassionate, coordinated, continuous, culturally effective, accessible and family-centered. A medical home allows primary care providers (i.e., pediatricians or family physicians), parents, child welfare professionals, and other stakeholders to identify and address all of a child’s physical and mental health needs promptly and as a team.

Benefits for Children

Medical homes benefit all children by providing a consistent, ongoing relationship with a primary health care provider and team who know the child well. This consistency is particularly helpful for children in foster care. A medical home preserves the relationship children have with their doctors and ensures medical records don’t get lost, even when they return home or change placements. Also, because they often have special health care needs requiring the services of many professionals, children in foster care derive special benefit from the coordination of care provided by a medical home. Other benefits provided by medical homes include:

- Doctor visits that aren’t rushed

- Easier access to specialists

- Improved quality of care, with fewer errors and preventable complications

- Less parental worry and burden

- Fewer hospitalizations and ER visits

- Less missed school and missed time from work

- More preventive health care

Endorsed by Federal Law

The medical home approach is embraced by physicians in North Carolina and across the country. Use of the medical home approach with children in foster care is also strongly supported by federal law. Part of the Fostering Connections to Success and Increasing Adoptions Act (HR 6893) directs states to establish a medical home and oversight of prescription medication, including psychotropic drugs, for every child in foster care (Center for Public Policy Priorities, 2008; Children’s Defense Fund, 2008). The overall goal of this provision in the law is to ensure continuity of health care for all children in foster care.

Practice Implications

To work for children and families involved with the child welfare system in North Carolina, the medical home approach needs you. Here’s what you can do:

Make sure the children you work with have a medical home. If their primary care provider (pediatrician or family physician) considers him or herself a medical home, the child has one. If the child does not have a medical home . . .

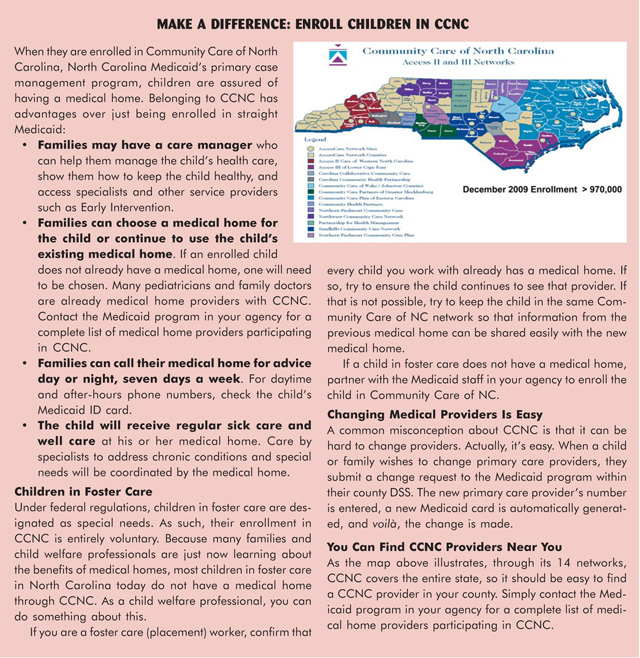

Educate Families. At every stage of child welfare work (Assessment, In-Home, Foster Care, and Adoptions) make a point of talking with birth and resource families about the benefits of medical homes. If they or the child are Medicaid eligible, encourage them to enroll in Community Care of North Carolina (CCNC). For more on this, see the box below.

For children in foster care who don’t already have a medical home: Work with the Medicaid staff in your agency. Partner with them to enroll the child in CCNC.

Know the medical homes in your community. Contact the Medicaid program in your agency for a complete list of medical home providers participating in CCNC.

Partner with medical homes. Make it clear to others that you understand the benefits of the medical home approach. Child and Family Team meetings (CFTs) are a great place to do this. The medical home approach is a natural fit with CFTs.

To Learn More

Select from the side bar at <www.medicalhomeinfo.org/tools/>

Special thanks to Betty West and Drs. Marian Earls, Gerri Mattson, and Emma Miller for their contributions to this article.