|

|

|

Vol.

17, No. 3

June 2012

Overcoming System Failure to Help Youth Find and Sustain Positive Relationships by Joan McAllister

Adapted f rom Fostering Perspectives, v. 13, n.1 (www.fosteringperspectives.org)

Despite improvements in foster care, most of us would not want our children placed in the custody of a county department of social services. Although foster care placement can be a lifeline, it can also permanently disrupt children’s positive relationships.

Too often, children removed from their homes lose contact with relatives, neighbors, school friends, teachers, pets and others who make up the constellation of their natural support networks. As these relationships are disrupted or broken during the removal process, children are expected to form new relationships in unfamiliar environments—with the foster parent, the new school, the new social worker, the new teacher—sometimes in a new town or at least in a new part of town. These experiences can have a negative impact on children’s ability to form and sustain connections to family and other supportive people.

Seven Outcomes for Teens

The NC LINKS program asks counties to focus on achieving seven outcomes for teens in foster care:

- Safe and stable housing

- Sufficient income to meet basic needs

- Educational and vocational training to secure stable employment

- Avoidance of high risk behaviors

- Postponed parenthood until emotionally and financially prepared

- Access to medical care and use of preventive care, and

- A personal support system of at least five caring adults in addition to professional relationships.

To learn more about achieving these outcomes, see North Carolina policy at http://bit.ly/O3WEZz.

Five Caring Adults

Evidence suggests that despite our efforts, there is room for improvement. For example, of the 611 young adults who aged out of foster care in North Carolina in 2007-08, we can only be sure that 316 (52%) had a support system of at least five caring adults at the time they left care.

We can do better. If an average group of adults are asked how many people are in their personal support system, most can list more than 40.

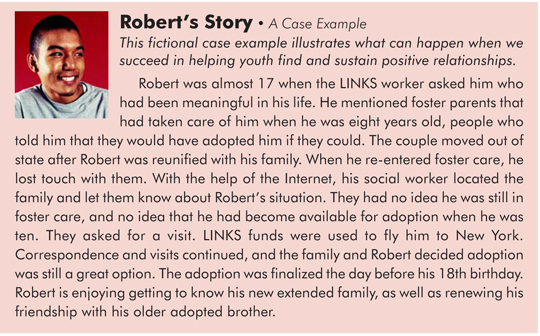

It’s not that people don’t care about youth aging out of care: many family members, friends, former foster parents, employers, teachers, coaches, and other caring adults would be willing to be a part of the youths’ lives—if they only knew about the need. Youth in foster care need at least the same opportunities as others to gain the supports they need to become successful adults.

Support Networks at Risk

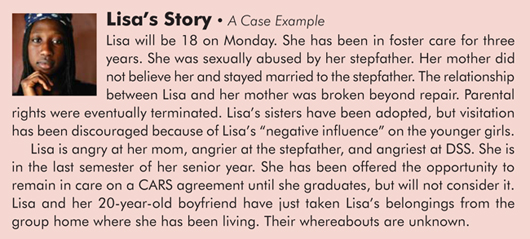

For children who, like Lisa in the case example above, are not reunified quickly, the damage caused by removal is often compounded over time. Foster care social workers may not be aware of the relationships that were lost and may not think to ask children about people who are or were important to them. They may rely on information in the child’s record, using other social workers’ judgments about the suitability of friends and relatives. In Lisa’s case, potentially untapped resources from her past include her sisters, their adoptive parents, her paternal relatives, and neighbors.

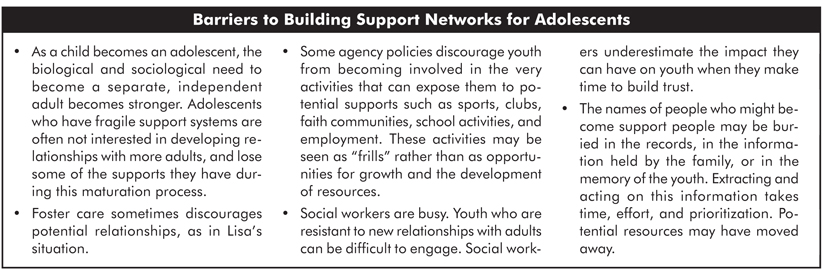

As youth remain in care, many miss out on opportunities to develop new supportive relationships. For example, some agencies have policies that require criminal records checks before youth in custody can visit overnight with families of friends. Some agencies refuse to allow youth to participate in sports or extracurricular activities because there is no approved means of transportation for the youth to return home, or because they are afraid that something bad might happen. Some youth are unable to attend their home faith community. Some are not allowed to work or volunteer without overcoming many behavioral and attitudinal hurdles. Additional barriers are listed in the box below.

Children entering foster care often lack basic personal supports; were that not true, many could avoid foster care placement or quickly move from foster care into the home of a relative or another caring, responsible adult. Those children who remain in foster care through adolescence face a combination of factors that, if not addressed proactively, are likely to lead to a lack of supports upon discharge.

What You Can Do

The most important thing we can do for children and youth in foster care is assure they have a consistent personal support network of at least five caring adults, in addition to those persons whose support is based on a professional relationship. If each of us makes the commitment to help youth identify and strengthen these relationships, we will literally help them survive the normal crises that everyone experiences on the path to adulthood.

The following strategies are recommended to help youth build their personal support networks:

- Ask the youth the names and contact information of people with whom they would like to re-establish or strengthen contact.

- Be particularly mindful of relatives and siblings as possible resources.

- Give youths opportunities to invite their personal supporters to their Permanency Planning Action Team or child and family team meetings. Don’t screen anyone out unless there is a clear safety issue.

- Ensure that youth attend their court reviews and that they communicate their plans and interests to the judge.

- Conduct “record mining” for the ten youth in your agency with the most fragile or non-existent support networks. Talk with the youth about names that are found that might be possible support persons.

- Use free and for-charge search engines to locate missing relatives and friends. Child Support Enforcement may already have access to information that could be used to find people. LINKS Transitional Funds* can be used to pay for searches for potential support persons.

- Keep your expectations, and those of the youth, reasonable. Your intent is to strengthen their support network, not to secure instant placement. If that happens, great—but people can be supportive in many different ways.

- Enable youth to participate in activities that will, among other things, expose them to caring adults. Avoid denying participation in these positive activities as a punishment for unrelated offenses.

- Remember that people can and do change. Immature parents often grow up and may become quite capable of being an adult friend to their young adult children. Stay open to the possibilities.

- Accept the young person’s plans for their life and help them develop those plans while they have the resources of the agency to help process what they are learning.

If youth are to have the best chance of transitioning successfully from foster care to adulthood, DSS must make a concerted effort to assure that existing relationships are maintained and strengthened throughout the youth’s time in care. We would want nothing less for our children—and these are our children.

*To learn more about LINKS transitional funds, contact Danielle McConaga (Danielle.McConaga@dhhs.nc.gov; 919/334-1110).

Training Resource: Real World Instructional Event

Real World Youth Events focus on career and lifestyle decisions, exposing youth in foster care to skills needed for job interviews and employment, continuing education, and budgeting. These powerful events give youth a chance for direct learning and practice.

Real World Instructional Events prepare foster parents, residential providers, social workers, and others to offer Real World Youth Events in their region. The next Instructional Event will be offered August 28-29, 2012 in Gastonia, NC. To register, log in to www.ncswlearn.org.