|

|

|

Vol.

20, No. 3

July 2015

Promoting Emotionally Healthy Parenting

As child welfare professionals, we may understand the damaging long-term effect of emotional maltreatment, and we may recognize that it is common among families we serve far beyond those who meet the legal standard for emotional abuse. Yet we may also feel ill-equipped to do anything to help.

Challenges clearly exist when trying to promote healthier parenting in families with a chronic pattern of harsh, negative interactions. At the same time, the steps we take to identify, understand, and shift harmful patterns in parent-child relationships can help families make meaningful changes, regardless of the type of maltreatment concerned. In fact, it may not be possible to assess or build any parent's protective capacity without understanding the degree of emotional response and nurturing they provide.

This article offers some suggestions for doing just that.

Trauma and Attachment

Children must feel safe (i.e., have psychological safety) before they can heal from trauma (NCTSN, 2013). Emotional abuse destroys this sense of safety. If we fail to identify and address emotional maltreatment in a child's environment, we make it difficult for them to recover from whatever it is that brought them to our attention.

All types of emotional abuse create an environment of toxic stress in which children feel physically and psychological unsafe. Without someone who consistently responds to their needs in a sensitive, timely way, children can't develop secure attachment. And without secure attachment, children come to believe that the world is unsafe, other people are untrustworthy, and they themselves are unworthy of love and protection. They also are left unable to regulate their emotions effectively, since this is a capacity that is developed physiologically in the context of a predictable, nurturing relationship. When these children eventually develop acting-out behaviors in an attempt to manage their fear and isolation, they often end up being labeled as "difficult" and exposed to progressively more punitive and less nurturing care (Benoit, 2004; Carlson, et al., 2003).

We see such cycles of toxic stress, insecure attachment, acting-out behavior, and maltreatment repeat across generations in some families. As anyone who has worked with such a family knows, traditional parenting classes are unlikely to stop this cycle (Barlow & McMillan, 2010). Until a parent can acknowledge and begin to heal from their own history of trauma, it is hard for them to understand how their behavior affects their children. To recognize this cycle in their family, parents need to explore how they perceive the parenting they received, the parenting they provide, and how the two are connected (Barlow & MacMillan, 2010).

However, before a parent is willing to go down this road, we must help them overcome barriers related to their difficult histories.

Building Trust

Many parents who respond to their children's needs in emotionally damaging ways don't do so intentionally. In fact, it is often not a conscious decision, but simply a result of the dysfunctional parenting that they received. Like their children, these parents often struggle with trust, fear of rejection and failure, and inability to regulate stress and emotions (Rees, 2010; NCTSN, 2011).

What does this mean for our relationship with them? As we do with traumatized children, we need to interpret parents' "resistant" or "oppositional" behaviors as signs that they are feeling threatened and misunderstood. Parents with histories of emotional abuse need us to show that we are attuned to their feelings, that we empathize with their reactions to us, and that we see the positive things they do and say to their children (NCTSN, 2011; Rees, 2010).

We can also anticipate that these parents may be unable to manage stressful situations without acting out or distancing themselves. When facing high stress situations such as foster care visits, court dates, or initiating treatment, it can help if we explicitly acknowledge with parents that it is a high risk situation for them, and then use solution-focused questions to help them come up with a plan for coping before, during, and after the event (NCTSN, 2011). Cooperative, encouraging practices, such as the use of child and family team meetings (CFTs) for planning and decision-making, can be especially helpful in engaging parents with trauma histories (Rees, 2010).

Of course, there is an inherent conflict between the time it takes to build trust and the timeframes and mandates of child welfare work (Rees, 2010). Realistically, CPS assessors may be able to identify some of the categories of emotionally abusive parenting that are happening in a family, but it is likely to be CPS in-home or foster care workers who have time to more fully assess the family's perceptions that lead to those types of interactions. With enough time and support, parents may be able to imagine and practice more healthy, sensitive responses to their children (Glaser, 2011).

Understanding the Family's View

An important part of intervening for emotional maltreatment is adjusting parents' overly negative or inaccurate beliefs about their children (Barlow, et al., 2008; Glaser, 2011). All parents have an internal "working model" about their children--how they view them, what characteristics they ascribe to them, the explanations they give for their behavior. Parents begin developing these models even before their children are born, as they learn about and prepare for their arrival. These models are strongly influenced by parents' own histories (Barlow, 2015).

Some parents who themselves were parented in negative ways have distorted views of their children. These parents then misunderstand or misread their child's behavior as "proof" of their negative view. For example, the parent may see her infant's crying as a sign that she's "spoiled" or "trying to drive me crazy" (Barlow, 2015; Glaser, 2011). It is important to identify such negative attributions by the parent, since they are a key barrier to secure attachment (Potter, 2014).

In extreme cases, parents may even develop a pathological view of the child, seeing typical child behavior challenges as signs that the child is bad or evil. Some therapists refer to this dynamic as "ghosts in the nursery," since the parent's own childhood is a constant but unseen influence on how they parent (Barlow, 2015).

The parent-child relationship is a two-way street, so it's also important to understand the child's perceptions. When talking with children, the goal is generally not to "prove" whether emotional maltreatment happened, but to elicit their feelings about themselves and their parents and learn what changes they would like to see in this and other areas of their lives.

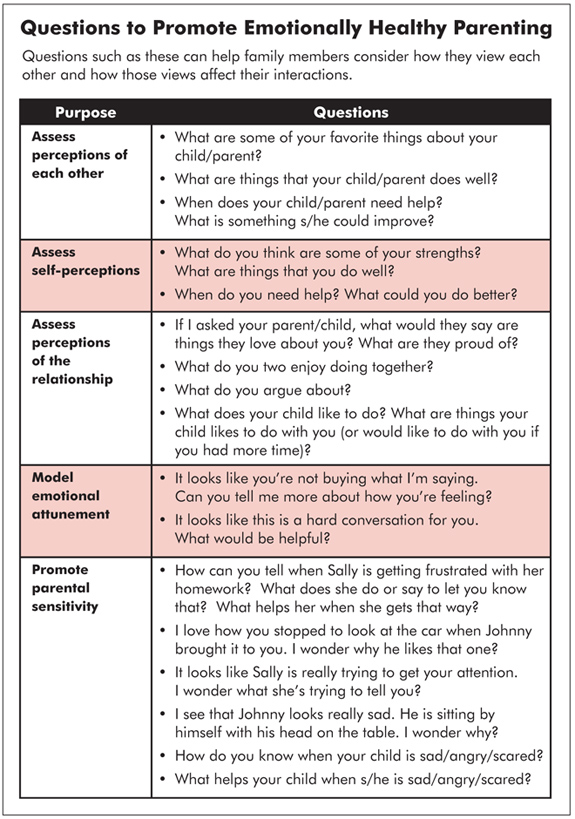

For examples of how to explore family members' perceptions of each other, see the box below.

Increasing Parental Sensitivity

When parents view their children through a distorted lens, the goal is to help them shift perspectives and see the world through the child's eyes (Dozier, et al., 2005). Parents who struggle with nurturing may react to situations based on their own poorly regulated emotions and needs, rather than on their child's needs. So an infant who needs a calm, soothing response may instead be ignored, or responded to with irritation or anger. This type of mismatch happens occasionally for every child, but in some families there is a chronic lack of attunement and sensitivity to the child's needs (Rees, 2010).

By taking a "wondering" approach, we can introduce parents to the idea of considering how their child experiences the world--and their parenting. This can involve simply asking parents how they interpret their child's signals. "I wonder why Jack is crying? What do you think he's trying to tell us?" When parents respond appropriately, even in small ways, we can make a point of recognizing what they did and how their child responded. "Wow! He really calmed down when you picked him up, didn't he? That must be just what he needed."

When parents express negative attributions about their child, we can correct them. "It sounds like Jack's dad does have a bad temper, but that's really different from what Jack is doing. Almost all 2-year-olds have tantrums, since they don't have a lot of ways to express themselves when they get frustrated. What do you think is going on that might be frustrating Jack?"

As many child welfare professionals know, for some parents even the most basic nurturing and caregiving behaviors do not come naturally. We can help build this capacity by wondering aloud about the signs the child is giving and labeling whether responses are helpful or not in meeting the child's needs. Rather than being an add-on to our work, such questions during our regular visits with families can in fact be the work. This type of conversation gets at the heart of protective capacity: parents must know how to read and respond to their child's needs if they are to protect them. Parents also need to understand both the positive and negative impact that their reactions can have on their children. Until they can see their interactions from both perspectives (their own and their children's), parents will likely continue responding in whatever way is familiar.

Parenting Programs

While at present there don't seem to be evidence-based parenting interventions focused specifically on emotional maltreatment, there are programs that address the underlying issues of attachment and parental sensitivity. Some of these are listed in the box below.

Programs that Promote Emotionally Healthy Parenting |

Evidence-Based Programs

Promising Practices

|

The Lifeline

Trying to address emotional maltreatment can feel overwhelming, but there is reason for hope. Research on resilience has shown over and over that many children manage to overcome traumatic histories and have positive outcomes (Delahanty, 2008).

Doyle (1997) reached a similar conclusion when she conducted in-depth interviews with college students in England who were survivors of emotional abuse or neglect. Each of them described their most important survival factor as having at least one "lifeline": someone "who gave unconditional, positive regard; someone who thought well of them and made them feel important" (p. 338).

Many children are able to reach out to the caring people around them, whatever their relationship, and experience the sense of being nurtured and loved. Even when we can't change long-term dynamics with birth parents, we can help children make these connections so they will know what an emotionally healthy relationship feels like.

Learning Resources |

|

For more on promoting healthy parenting, look for these classes on ncswLearn.org: |

|

|

Assessing and Strengthening Attachment |

|

Visitation Matters This is a two-day classroom training that includes information and practice to prepare families for healthy interactions during visits and effectively integrate shared parenting, family culture, and facilitation skills for successful visits that reduce trauma and improve outcomes for children. |