|

|

|

Vol.

26, No. 1

December 2020

Safety Organized Practice: North Carolina's New Practice Model

After North Carolina's legislature passed Rylan's Law (HB 630) in 2017, North Carolina contracted with the Center for the Support of Families (CSF) to develop social services and child welfare reform plans. CSF's recommendation in the child welfare reform plan for a statewide practice model was for North Carolina to develop clear and well organized practice standards for Safety Organized Practice (SOP). This article describes what our state has done to follow through on this recommendation.

Practice Models

A practice model--sometimes also referred to as a practice framework--details the values and principles that guide a system's approach to working with children and families. Practice models describe activities and techniques critical to achieving desired outcomes (CWPG, 2008).

Using practice models helps child welfare agencies by:

- Ensuring staff know what their jobs are and how to do them.

- Helping staff, families, and other stakeholders (e.g., courts, providers, etc.) understand the agency's purpose and what it does.

- Promoting consistency by aligning service provision, training, quality assurance, and policy creation under a single philosophical vision.

- Ensuring staff at every level know agency procedures, policies, and practices. This helps them hold themselves and others accountable.

- Helping staff make critical decisions, even in unusual circumstances.

(NCWRCOI & NRCPFC, 2008)

|

Watch this brief video from the National Child Welfare Workforce Institute (2020) to hear the story of how an Indiana agency returned to its core values and mission by rallying around their practice model. |

Safety Organized Practice

SOP combines elements of two other well-known practice models, Signs of Safety and Solution-Focused Casework, with the Structured Decision Making (SDM) system North Carolina has been using for years (Meitner & Albers, 2012). In addition to tools from the above models, SOP incorporates elements from other approaches such as motivational interviewing, solution-focused therapy, appreciative inquiry, and cultural humility.

North Carolina chose SOP as its practice model for two main reasons:

1) The Structured Decision Making tools North Carolina has used for years are outdated. As part of implementing SOP, the National Council on Crime and Delinquency (NCCD) will update and empirically revalidate our state's SDM tools.

2) Many SOP tools are consistent with North Carolina's values of being safety-focused, trauma-informed, family-centered, and culturally competent and include specific strategies for working collaboratively and effectively with families to assure children are safe. Examples of tools that fit our values include Harm and Danger Statements, The Three Houses, and Safety Mapping.

Examples of Tools from Safety Organized Practice |

The Three Questions. These are: What are we worried about? What is working well? What needs to happen next? Harm Statements, Danger Statements, and Safety Goals. These statements rely on critical thinking and using behavioral details rather than jargon to keep stakeholders focused on what happened, what the concerns are, and what needs to happen for the child to be safe now and in the future. The Three Houses. Developed with the child, the House of Good Things, the House of Worries, and the House of Hopes/Dreams help the worker learn about danger and safety from the child's perspective. The Safety House. Developed by the child, the Safety House is a tool to include the child in safety planning; it illustrates the child's desired state regarding who lives in the house, what activities go on in the house, the rules of the house, who can visit, who should not be allowed in the house, and the safety path. Circles of Safety and Support. This tool helps identify and build a family's safety network. (Casey Family Programs, 2019) |

Current Status

The ULT has selected and defined five essential functions performed by frontline workers, supervisors, and leaders from the beginning to the end of child welfare services that will help North Carolina live into its commitment to provide safety-focused, trauma-informed, family-centered, culturally competent services. Supported by CSF, North Carolina's Design Teams have begun providing input into the behaviors stakeholders would like to see included in practice standards. Additional input is being gathered from youth and family members with lived experience with child welfare, frontline workers who provide services, and state staff responsible for training and coaching. When completed, the practice standards will describe in behaviorally-specific terms how staff will engage and work with children and families and how supervisors and agency leaders will support workers and create conditions for success.

Learning the practice standards will build skills and behaviors in the workforce that are fully consistent with SOP. The practice standard will anchor SOP, provide a foundation for learning and using SOP tools, and help guide decisions on selection and implementation of those tools in North Carolina. Other states--including California where much of SOP was developed--have had success taking a similar approach.

The goal is to finalize practice standards by June 2021 and complete training on the practice standards by June 2022. The timeline developed with NCCD for the implementation of SOP calls for revalidating and implementing updated SDM tools by spring 2022 and beginning training on other SOP tools in summer 2022.

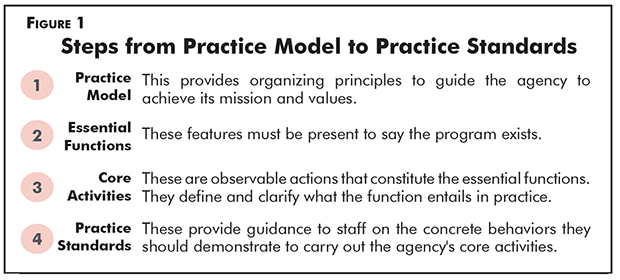

Figure 1 outlines the relationship between a practice model, its essential functions, core activities of those functions, and practice standards.

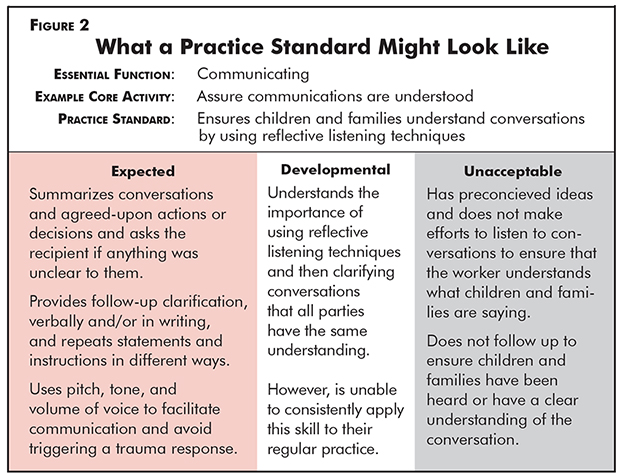

See Figure 2 for a hypothetical example of what a finished practice standard may look like.

There are the five essential functions in child welfare as selected and defined by the ULT:

Communicating: Timely and consistent sharing of spoken and written information so meaning and intent are understood in the same way by all parties involved. Open and honest communication underpins all essential child welfare functions.

Engaging: Empowering and motivating families to actively participate with child welfare in the functions of assessing, planning, and implementing by communicating openly and honestly with the family, by demonstrating respect, and by valuing the family's input and preferences. Engagement begins on first meeting a family and continues throughout child welfare services.

Assessing: Gathering and synthesizing information from children, families, support systems, agency records, and persons with knowledge to determine the need for child protective services and to inform planning for safety, permanency, and well-being. Assessing occurs throughout child welfare services and includes learning from families about their strengths and preferences.

Planning: Respectfully and meaningfully collaborating with families, communities, tribes, and other team members to set goals and develop strategies based on the continuous assessment of safety, risk, and family strengths and needs through a child and family team process. Plans should be revisited regularly by the team to assess progress towards goals and whether changes are needed.

Implementing: Carrying out plans that have been developed. Implementing includes linking families to services and community supports, supporting families to take actions agreed upon in plans, monitoring to assure plans are being implemented by both families and providers, monitoring progress on behavioral goals, and identifying when plans need to be adapted.

Statewide Implementation

Once North Carolina's child welfare practice model is complete, statewide training will occur and the practice standards and tools will be used to assess performance and develop the skills of leaders, supervisors, and frontline staff.

A specific timeframe for statewide implementation of the practice model has not been determined. However, implementation will almost certainly occur in phases and be aligned carefully with implementation of the Family First Prevention Services Act.