|

|

|

©

2006 Jordan Institute

for Families

Vol.

11, No. 2

February 2006

A History We All Should Know

To understand and successfully engage American Indian families you must know something of their history. This is a brief overview.

Extermination

Before 1871, the U.S. government used warfare and other means to try to eliminate the “Indian Problem.” Tribes that survived were removed from their lands and forced onto reservations (Halverson, et al., 2002).

Assimilation

After 1871 the government policy toward Indians changed to one of assimilation (Halverson, et al., 2002). Boarding schools were an essential part of this policy. From the 1870s through the 1930s many Indian children were taken from their families and raised in harsh, rigid institutions, the primary purpose of which was to “civilize” Indians and eradicate all traces of Native culture.

In boarding schools children were beaten for using their native language. Their hair, an important cultural symbol, was cut short. They were required to wear uniforms instead of individually created and uniquely decorated clothes. Their names were taken away and they were given new “American” ones. Many schools, even government ones, required children to engage in Christian worship. Many children lost all contact with their parents, grandparents, and extended families (Horejsi, et al., 1992).

|

|

|---|---|

| Photos courtesy of the Western History/Geneaology Department, Denver Public Library | |

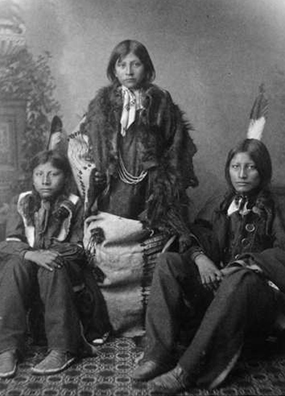

Above: Boarding school “before and after” photos. The schools aimed to destroy American Indian culture without killing individual children. Their legacy is a trauma of shame, fear, and anger that is still felt today. |

|

The boarding schools can be seen as a continuation of the war on Indians, only the focus had shifted to the children (Keohane, 2005). An example of the ruthlessness of this war was the fact that from 1910 to 1930 the government offered bonuses to boarding school workers to kidnap Indian children from their homes and take them to boarding schools. These workers were known as “kid snatchers” (Goldsmith, 2002).

The boarding schools had a devastating effect on Native families, in part because they prevented the passing on of traditions and knowledge about how to raise children and be a family. In addition, the schools introduced new and dysfunctional behaviors, such as the use of severe physical punishment of children, which previously was rare among the tribes. Many children were also subjected to sexual abuse (Horejsi, et al., 1992).

“Many of the boarding school survivors returned to their tribes/nations and were unable to pick up the thread of family life, inadvertently continuing the legacy of abuse they themselves experienced away from home” (Fox, 2004).

Boarding schools were phased out after an official report criticized government policy for educating Indians. Although the boarding school era ended around 1940, the resulting trauma, shame, fear, and anger—and related social problems—continue to ripple through the generations, hurting Indian families and children today (Kalambakal, 2001; Andrzejek, 2004).

Adoption and Foster Care

In the years after 1940 the push to get American Indians to assimilate continued. Adoptions and child welfare intervention were a significant part of this effort.

From the 1950s to the 1970s many private organizations tried to “save” Indian children by removing them from their homes and placing them for adoption in non-Native homes (Goldsmith, 2002).

At the same time, Indian children were placed in foster care at shocking rates: a 1969 survey conducted in 16 states with large Indian populations found that between 25% to 35% of all Native children were removed from their families and placed in foster or adoptive homes. In some states Native children were 13 times more likely to be removed from their homes than non-Native children (Goldsmith, 2002; CWLA, 2005). The majority were placed in non-Native foster homes.

Statistics such as these, as well as ten years of hearings, led Congress to pass the Indian Child Welfare Act of 1978. For information about this law and how it applies to you, read the article on ICWA in this issue.