|

|

|

©

2007 Jordan Institute

for Families

Vol.

12, No. 3

June 2007

A Rural Success Story

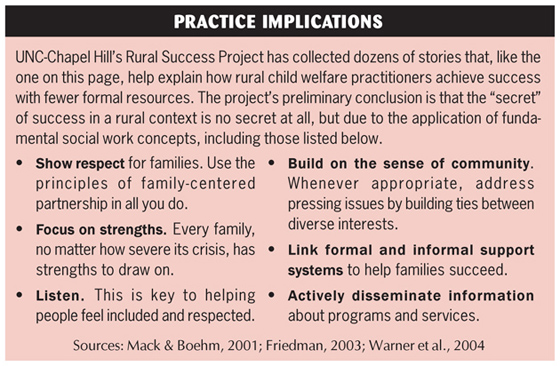

Though essential, data analyses alone cannot give us a full appreciation for the achievements of rural child welfare agencies. For this we need stories as well as facts. Therefore we present the following example of successful child welfare practice in a rural context. This story was collected by UNC-Chapel Hill’s Rural Success Project team. To protect confidentiality, the family’s names have been changed.

Swain County Department of Social Services Program Manager T.L. Jones remembers the day last spring when he and one of the agency’s CPS social workers responded to a child maltreatment report. At the home, they found what he later described as a seemingly hopeless, dark dungeon.

Inside were Cassie and Billy, a young couple, and their two children, both under age two. The report had been about children sorting through garbage for something to eat, but it quickly became evident Cassie and Billy were battling a severe addiction to methamphetamine. They had no jobs and faced possible eviction.

Billy, relatively sober, was “watching” the children. Cassie was in a stupor on the couch, drooling. Her hands were swollen from sticking needles between her fingers, shooting up.

Cassie and Billy were in trouble. They cared deeply about their children, but they did not know how to stop using drugs or how to start putting their life back together. Thinking back, Cassie says, “Life was there, but it wasn’t there. It’s like waking up in the morning, you see your family and things go right one day. And then the next day things would just drop.”

Cassie and Billy also remember the first encounter with DSS and how angry they were when the boys were removed from their home and placed with Cassie’s extended family. Cassie says after she got over being mad she started blaming everybody else, not wanting to look at herself.

Social worker Lisa Enloe, who was assigned to work with them, says that at first they were a family “that would run and hide from us.” Yet eventually they started coming to DSS every day asking, “What can we do now?”

Billy attributes their eventual success not only to his and Cassie’s relentless drive to get their kids back, but also to Enloe, who held them accountable while simultaneously respecting and listening to them.

Billy says Enloe “told us what we had to do—sat down and listened to our side—I mean just being a friend to us. She showed us what we need to do to get our kids back and been there for us and kind of guided us down that path.”

Enloe adds that Cassie and Billy were creative, too. When Cassie could find no in-patient treatment options in the Swain County area she attended a program in Knoxville, Tennessee. She later joined an outpatient program on the Qualla Boundary. Billy attended an intensive outpatient program two counties away from the couple’s home. They eventually stopped using and have been clean for months.

Billy has a steady job as a cook. Cassie’s made peace with her mother, from whom she was estranged. The children returned home in time for the holidays—less than a year after they were taken into DSS custody.

“It feels wonderful,” Billy says.

Swain County DSS is happy, too. This family’s story, Jones says, “Reminds me that not every case is hopeless that looks like it’s hopeless. I am not naïve enough to believe that we can make every case turn out like this, but it gives you that little glimmer of hope that maybe we can take what seems to be a hopeless case and turn it around.”