|

|

|

©

2007 Jordan Institute

for Families

Vol.

12, No. 4

August 2007

Family Courts in North Carolina

The preceding article described how attitudes about justice for juvenile offenders have shifted over the years, moving away from rehabilitation and towards punishment. The dominance of the punitive model of juvenile justice is by no means complete, however. Today a very different approach to handling juvenile justice, child welfare, and other family-related legal proceedings is making headway across the U.S. In North Carolina this approach is called Family Court.

Family Courts

Family Courts emerged in the 1990s in an attempt to improve the way courts handle domestic cases. Specifically, Family Courts are an effort to embrace and implement certain approaches to judicial procedure and the handling of court cases in order to:

- Respond more effectively to the increasingly complex challenges faced by families and children involved with the judicial system (Future Commission, 1996).

- Improve the experiences of children during the court process, especially children involved with the child

welfare system (Kirk & Griffith, 2006). - Expedite permanence and achieve other desirable child welfare outcomes (Kirk & Griffith, 2006).

- Address court administration issues, particularly the overcrowding of District Court dockets.

How They Work

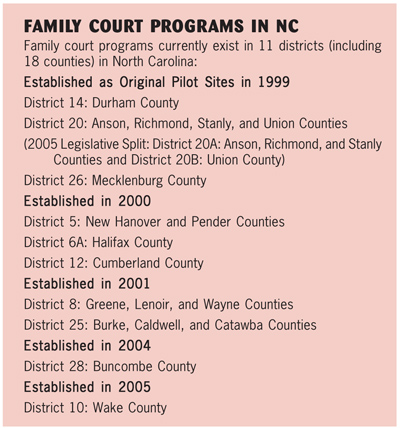

Family Court programs exist in 11 North Carolina districts (see box). In each district they operate under the auspices of the Chief District Court Judge, with support from the Court Programs and Management Services Division of the NC Administrative Office of the Courts.

North Carolina’s Family Courts hear issues relating to the families assigned to them. This includes juvenile delinquency; child maltreatment and dependency; termination of parental rights; domestic violence; child custody and visitation rights; and divorce and related financial issues such as child support, alimony, and equitable distribution of property.

In terms of day-to-day operations, the local chief District Court judge administers each Family Court. He or she is assisted by a Family Court administrator and one or more case coordinators assigned to domestic and juvenile court.

How Are They Different?

Following are some of the things that make Family Courts different from traditional District Courts. However, it is important to note that because each Chief District Court Judge has a great deal of discretion, practices vary among North Carolina’s Family Courts.

Philosophy. The mission of Family Court is to (1) help resolve cases involving children and families through

combined efforts of the family, the Court, and community services, (2) approach each case in a way that is not

overly adversarial or intrusive but always in a just, timely, and efficient manner, and (3) be courteous, safe, and accessible and to provide quality service to those in need (Family Court Advisory Committee, 2007).

Timeframes. The goal of Family Court is to resolve all cases within one year of filing.

Management. In Family Court, the court sets the calendar and manages the case from filing to disposition. Both judges and court staff receive extensive training on the fundamentals of effective case flow management (AOC, 2007).

Family Court Administrators. Some child welfare agencies have been able to resolve longstanding concerns about their interaction with the court system (e.g., long, unproductive wait times for workers on court days) by working closely with their Family Court administrator.

One Judge, One Family. In Family Courts, a recommended best practice is to have a single judge (or team of judges) assigned to each family. He or she hears every issue involving that family, whether it is divorce, child

custody, child maltreatment, dependency, or delinquency.

Chief District Court Judge H. Paul McCoy, who administers the Family Court in District 6A (Halifax County) says this approach “helps the case proceed through the court more expeditiously since the judge is familiar with the family and the case file and only has to go forward from the last order in the file rather than reviewing the entire file to familiarize himself with the case.”

Day One Conferences. Another recommended best practice being applied in some Family Courts, Day One Conferences (also called “child planning conferences”) are court-facilitated gatherings held soon after the filing of an abuse/neglect petition. These events bring everyone—including schools, DSS, mental health, parents, Guardians ad Litem, and the courts—to the table in a relaxed, respectful environment. The purpose of these meetings is to determine if placement can be found with family or friends, what services need to be initiated immediately to expedite resolution of the problems that led to the removal of the children, and to establish a visitation schedule appropriate to the developmental needs of the children and the circumstances of the family (AOC, 2006).

Many times, the things decided in these conferences are what families and other parties choose for themselves. This can feel much better to families than having things mandated by the court. One child welfare professional told us that as a result of Day One Conferences, “Ninety-eight percent of the time we are able to have an agreement in place before we go in front of the judge.”

In their 2006 evaluation of North Carolina’s Family Court pilots, Kirk and Griffith identified Day One Conferences as the most important component of Family Court when it comes to child welfare cases.

Emphasis on Services. Many Family Courts use mediation and other dispute resolution programs to resolve issues so the court does not have to issue a judgment or order. However, when a judge does need to hear matters or issue orders involving a family, case coordinators ensure there is nothing to delay the prompt resolution of the issue before the court.

Local Family Court Advisory Committees. These advisory committees, which usually meet two to four times a year, serve as an important way for stakeholders (including DSS) to bring their concerns to the attention of the Family Court and to suggest strategies for resolving these concerns and any other issue the court raises with them.

Do They Deliver?

Do Family Courts do a better job than traditional District Courts when it comes to achieving positive outcomes for families and children?

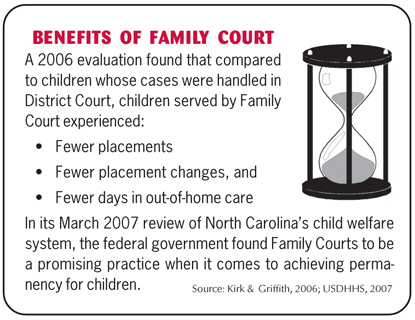

If your focus is on child welfare outcomes, the current evidence suggests the answer is yes. Kirk and Griffith found that children whose cases were handled by Family Court experienced fewer placements, fewer placement changes, and fewer days in out-of-home care than children whose cases were handled in District Court.

They also concluded that Family Courts performed better than traditional District Courts on most court functions. For example, they found the Family Courts they studied generally “required fewer judges per child case, more rapidly connected families with court resources, utilized fewer court days per completed hearing by limiting the number of continuances granted, and achieved case milestones more rapidly than the comparison District Courts” (National Child Welfare Resource Center on Legal and Judicial Issues, 2007).

This certainly fits with the experience of Halifax County. According to Judge McCoy, the average time it takes a domestic case to move from filing to disposition in the 11 Family Court districts in North Carolina is 113 days. Statewide, in the non-Family Court districts, the average is 313 days. In Judge McCoy’s district the average is 59.5 days. (Note: this is for domestic cases—usually timeframes for abuse, neglect, and dependency cases are longer.)

Carolyn Poythress, Program Administrator for Child Welfare Services at Halifax County DSS, believes Family Courts have helped her agency achieve more timely and successful outcomes for children. She says that together Family Court and the Multiple Response System (North Carolina’s child welfare reform effort) are redefining the way we engage families and children and raising awareness about families’ needs.

Poythress points out that most of the time, even before it gets to Family Court, DSS has already “helped the family understand that we are not out to get them and if we get to court, it is because we had no other option. The families’ being able to see us as advocates from the beginning is making what we do more successful.”

To learn more about Family Courts in North Carolina, visit <www.nccourts.org>.