|

|

|

Vol.

20, No. 1

December 2014

Research on Kinship Care: Implications for Practice

Formal kinship care occurs when "children are placed in the legal custody of the State by a judge, and the child welfare system then places the children with grandparents or other kin. In these situations, the child welfare agency, acting on behalf of the State, has legal custody and must answer to the court, but the kin have physical custody....Relative caregivers have rights and responsibilities similar to those of non-relative foster parents" (CWIG, 2010).

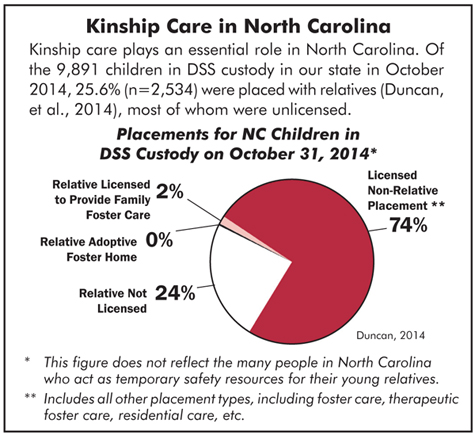

Child welfare agencies in our state rely heavily on formal kinship care. As the figure below shows, today one in four children in the custody of a North Carolina county DSS is cared for by a relative (Duncan, 2014).

Given the important role it plays, it makes sense for us to understand what the research says about kinship care, and to carefully consider the implications for child welfare workers and their agencies.

Kinship Families

Kinship providers vary widely in their relationships to the children they care for. They include grandparents, aunts, uncles, young relatives, and other kin, as well as close friends who are like family (i.e., "fictive kin").

Kinship care providers are as diverse as the population of North Carolina. Although they all have many strengths--they would not be asked to care for vulnerable children if they did not--as a group kin caregivers have traits that have been known to make parenting harder: they are often older, poorer, single, and have less formal education than non-relative caregivers (Ehrle & Geen, 2002). They also report more health problems and higher levels of depression (sources cited in Winokur, et al., 2008).

Kinship Care Outcomes

Placement Stability and Permanency. Children placed in kinship care experience more stability than those placed in non-relative foster care (Farmer, 2009; Koh, 2009; Gleeson, 2007; Cuddeback, 2004). Overall, children in kinship care tend to have fewer placements and experience less placement disruption (Winokur, Holtan, & Batchelder, 2014).

In the largest systematic review of the literature to date--which analyzed 102 of the methodologically soundest studies that have been done on kinship care--Winokur, Holtan, and Batchelder (2014) found no difference between kinship care and foster care when it comes to the length of time children spend in out-of-home care or rates of reunification. However, they did find differences in other means used to achieve permanence for children. Children in foster care were more likely to be adopted, while children in kinship care were more likely to achieve permanence through guardianship.

Safety. Most studies agree children in kinship care are as safe--if not more so--than children placed in non-relative foster care. In their literature review, Winokur, Holtan, and Batchelder (2014) concluded children are actually safer in kinship placements. In the studies these authors examined, children in foster care were 3.7 times more likely to be maltreated by their temporary caregivers than were children in kinship care.

Well-Being. When it comes to well-being, kids in kinship care seem to do better than those in foster care. Based on outcome data from the rigorous studies they reviewed, Winokur, Holtan, and Batchelder conclude that children in kinship care experience fewer behavioral problems, fewer mental health disorders, and better well-being.

Children in foster care do have better access to mental health services. They are more than twice as likely as children in kinship care to receive mental health services. Winokur and colleagues (2014) speculate that "training and supervision of foster parents may contribute to the higher identification of mental health problems, and as such contribute to higher levels of service utilization."

Other findings relevant to well-being: studies have found that compared to children in non-relative foster care, children in kinship care are more likely to be placed with siblings (Berrick, et al., 1994; Testa & Rolock, 1999), to perceive their placements positively (NSCAW, 2005), and to visit siblings and parents (sources cited in Geen, 2003).

Service and Support Needs

The outcomes experienced by children in kinship care are all the more impressive when you consider that many kinship caregivers may have unmet service needs. In general, studies agree kinship caregivers have fewer resources and receive less training, services, and financial support than non-kinship caregivers (Cuddeback, 2004).

Sometimes lack of awareness is the issue. For example, there is some evidence kinship caregivers may be less familiar with the mental health system and thus more inclined to try to address mental health/behavioral issues on their own. Research also suggests child welfare workers may be less likely to offer mental health services to children placed with kin (Cuddeback, 2004).

Other studies found that when children are placed with kinship providers, workers visit less often, are more ambivalent, and are less clear about their role (AIA National Resource Center, 2004; O'Brien, 2012).

In addition, several studies have found notable differences between workers and caregivers in their perceptions of what constitutes quality care. Workers tend to focus on safety as the primary indicator of quality care, while kinship caregivers focus on the child's school performance, behavior, and happiness. This discrepancy may create barriers in relationships between workers and kin caregivers (Gleeson, 2007).

Implications for Agencies and Practitioners

Here are some recommendations for agencies and practitioners based on the research reviewed in this article:

- Know that kinship care has some strong upsides: compared to non-relative foster care, it is a more effective way to enhance children's placement stability and well-being, especially their behavioral development and mental health functioning.

- Understand the trade-offs. Historically, children in kinship care take longer to achieve permanency and have lower service utilization rates than children in foster care. When agencies place children with kin, they need to continue diligent permanency planning efforts, license kin whenever possible, and always ensure robust service provision.*

- The decision to use kinship care should always be individualized, taking into account the specific child's needs and the caregivers' ability to meet those needs.

- Don't write off foster care. Foster care also produces positive outcomes for children; it is still a viable option, especially when a kinship placement isn't possible.

- As an agency, discuss the differences between the kinship and non-relative foster care providers you work with. Explore ways to increase levels of caseworker involvement and service delivery with kinship placements. This may help you do a better job meeting caregivers' needs, making kinship care even more effective.

- Know what our state and county policies are regarding financial support for kinship caregivers. Ensure kinship providers get the information they need to take advantage of all available resources.

- When assessing and supporting relative placements, consider and address the kinds of needs commonly experienced by kinship care providers.

- Notify relatives when children enter foster care. See the next article for ideas.

Policies Can Powerfully Influence Outcomes |

|

Research suggests policy can have a huge impact on kinship care and the outcomes it achieves. In one study, researchers used matched samples to compare the results of kinship care in five states. The differences found led researchers to speculate that state-specific policy and practice regimens might have more impact on children's ability to achieve legal permanence than the type of placement the children received (Koh, 2009). Nationally, states take different approaches to kinship care policy. This has led to different definitions, differences in funding options, and a wide array of licensing requirements. In some states, attempts to standardize have produced a one-size-fits-all approach to placement providers, resulting in unfair practices that don't meet kinship providers' needs (AIA National Resource Center, 2004). There seem to be no easy kinship care policy fixes. Policy areas the field continues to wrestle with include: Financing and funding. Debates focus on how to provide financial support to kin caregivers without creating a disincentive for reunification or other permanency options (Ehrle & Geen, 2002). Service delivery approaches. We need a service delivery model that meets kinship caregivers' needs. A key question: How do we support kinship providers when they are not licensed and child welfare agencies do not formally supervise them (O'Brien, 2012)?

|

References for this and other articles in this issue

* On Dec. 15, 2014 this bullet was revised to make it clearer that the difference in permanency outcomes for kinship and non-relative foster care may be due to differing levels of service provision.