|

|

|

Vol. 29, No. 1

February 2026

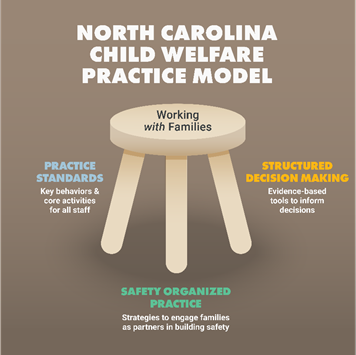

Safety Organized Practice and North Carolina's Practice Model

North Carolina has adopted a practice model to help our child welfare system shift from doing to families to working with them. As the figure shows, this model is supported by three components, just like a three-legged stool. One leg is the child welfare practice standards. Another is policy, which includes the use of the revised Structured Decision Making tools. In this article, we zero in on the third leg, Safety Organized Practice tools and strategies that strengthen partnerships with families and communities while keeping child safety at the center.

Practice Model Components

North Carolina's practice standards describe how leaders, supervisors, and workers should interact with children, youth, families, and other child welfare staff. Each standard has key behaviors and core activities that staff at all levels should practice. They include:

Communicating - how to listen, share information, maintain transparency, build trust

Engaging - involving children, families, relevant stakeholders; building rapport and partnerships; investing in staff well-being and development

Assessing - evaluating safety, risk, needs, strengths; ongoing monitoring to assess performance

Planning - creating a case/family plan that includes safety goals, permanency, and well-being; mapping out interventions and responsibilities, and is inclusive of families, staff, and partners

Implementing - putting the plan into action; monitoring progress; making adjustments; ensuring services are delivered; celebrating success

Click here to read more about tools supporting the implementation of practice standards.

Structured Decision Making (SDM) tools are evidence-based assessments and protocols that guide and inform child welfare decisions. SDM tools promote consistency, objectivity, and alignment with best practices. Counties are actively implementing the following revised SDM tools: Screening and Response, Safety Assessment, Family Risk Assessment of Child Abuse/Neglect, and the Family Strengths and Needs Assessment, a component of which is a new Child Strengths and Needs Assessment.

Safety Organized Practice (SOP) supports the implementation of the practice standards and SDM tools by providing a consistent framework that engages families as partners in building safety. SOP has three major objectives: (1) developing good working relationships, (2) using SDM tools and critical thinking, and (3) building collaborative plans that enhance daily child safety. Like the practice standards, SOP emphasizes plain, transparent language so that families, children, and professionals all understand what has happened, what is currently being assessed, and what needs to change.

SOP Tools

The following SOP tools blend structure with collaboration to improve the child welfare outcomes of safety, permanency, and well-being.

Three-Column Mapping

Three-column mapping is a cornerstone of SOP. This tool organizes conversations into:

What are we worried about? (harm and worry)

What's working well? (strengths and protective capacities)

What needs to happen? (safety plans and next steps)

This structure balances concerns with strengths, ensuring families are recognized not only for their challenges but also for their resilience and capacity for change. For more on three-column mapping, click here.

Harm and Worry Statements

Provisional harm and worry statements are developed during Screening and Response to help families, children, and networks understand concerns in concrete terms. They are called "provisional" because the information that's been reported has not been confirmed through a CPS assessment yet. These statements identify the caretaker, the negative behavior they are exhibiting, and the impact or likely impact of the behavior on the child. Harm statements summarize a report of an impact that has occurred on a child. Worry statements focus on the future (i.e., what the agency is worried will happen to the child if nothing changes). Here is an example:

Harm - The reporter stated that Ms. Smith left her child, Betty (7), home alone overnight. Betty stated to the reporter that she was scared to be alone.

Worry - Betty could be hurt by an accident and feel scared without an adult to care for her if she is left alone overnight.

As the case is assessed, and danger indicators are identified on the Safety Assessment, harm and worry statements continue to be noted on the Safety Plan. They help the family understand why child welfare is involved in their lives, and they connect to what needs to change through the development of a safety plan and, if needed, through continued case planning. To learn more, take the e-learning Provisional Harm and Worry Statements at Intake as well as Harm, Worry, and Goal Statements.

Safety Plans

Safety plans are written as observable, measurable actions adults will take to ensure children's ongoing safety. Action steps in safety plans go beyond intentions; they are commitments that can be demonstrated and monitored over time.

For example, "Ms. Smith will make sure Betty is safe" is a vague action step/commitment. A more concrete commitment might be: "Betty will always be cared for by a safe adult-such as her mother, grandmother, or neighbor-who will stay with her overnight and make sure she has meals and supervision."

SOP calls for families to help write and agree to the safety plan goals. Once goals are drafted, workers should ask the family questions to confirm they are realistic and achievable. For example, a worker might ask: "If you had to work late tonight, what exactly would happen? Who would call Grandma? Who would stay with Betty? What would Betty know about the plan?" Practicing in advance shows whether the plan is realistic and gives everyone confidence that it will work.

Another way to initiate a discussion on whether a safety plan is realistic and achievable is by asking scaling questions to assess a parent's willingness, capacity, and confidence with the plan. For example:

Willingness - "On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means you are unwilling to have your neighbor stay overnight with Betty, and 10 means you are totally willing, where are you?"

Capacity - "On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means 'I can't transport/pickup Betty to/from childcare', and 10 means 'I have no barriers to getting Betty to/from childcare', where are you?"

Confidence - "On a scale from 0 to 10, where 0 means you are not confident at all that this plan will work and 10 means you are totally confident, where are you?"

These questions will help understand if the family believes the plan will be successful and provide an opportunity for a caseworker to ask for more information: "What would it take/what support do you need to increase your answer by one more point?" Safety plans are not static. They are living documents that evolve as circumstances change and progress is made. A caseworker should continue to ask about the family's perceptions and the continued support needed to remain successful.

Building Safety Networks

A strong safety plan cannot rely on child welfare alone. SOP prioritizes creating a safety network-extended family, friends, and community members who support the family and help monitor safety. These networks make safety plans sustainable long after child welfare involvement ends. Here is an example:

Betty feels safest when her mother, grandmother, or neighbor is around. The worker helps the family create a safety network that includes them. Together, they agree on who will stay overnight if the mother is away, check in with Betty to make sure she feels safe, and be available to support her if she feels scared.

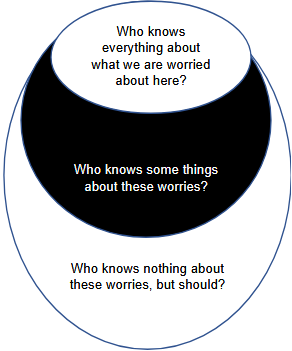

If the family is having difficulty identifying people in their safety network, use a visual tool such as a Circles of Safety and Support diagram to help identify who is in the family's inner circle, middle circle, and outer circles of support. Ask prompting questions such as:

Inner - Who are the first people you call when you are in need?

Middle - Who supports you a little?

Outer - Who have you not reached out to? What would it take to move them to your inner circle of support?

Building and using safety networks reduces isolation and spreads responsibility for safety across a natural support system. To learn more, click on Using Circles of Safety and Support to Create Safety Networks with Families.

Solution-Focused Practice

It is easy to focus on problems. Usually, we are involved with families because a problem was identified and a report was made. SOP encourages solution-focused practice to increase opportunities for solutions; it invites people to think about the way they resolve problems. When child welfare staff use solution-focused questions with families, they empower the family, not the problem. These questions uncover times when problems were managed differently (exceptions) and concentrate on strengths and solutions that the family identifies. This helps families envision and build their own solutions. For more on solution-focused questions, click here.

Tools Engaging Children

Children's voices matter. SOP includes the following age-appropriate tools to ensure children understand what is happening and can contribute to the planning process.

Three Houses. This tool helps workers engage with a child or youth during a CPS assessment and safety planning. There is a House of Worries, a House of Good Things, and a House of Hopes and Dreams. Let the child decide where to start. For example, ask them to draw, write, and/or describe what good things are happening in their home. Use one sheet of paper per house. For more on the Three Houses tool, click here.

Safety House. This tool should be used as part of a collaborative safety planning process throughout the child welfare service continuum. For example, invite a child to draw themselves in the center of a house. This reinforces that our focus is on the child and how they experience and feel about the world around them. Ask them to fill in the blank space between the walls with things that they enjoy or like about their house and family, such as traditions, routines, and people. Draw an outer circle around the house and ask the child to think about whom they like visiting the house. Draw a red circle to the side. These are people whom the child does not want to allow inside the house, such as unsafe people or threats to their safety. The roof of the Safety House is the rules. Invite the child to create rules for their safety house.

Conclusion

Safety Organized Practice is more than a set of tools-it is a mindset. It creates shared understanding, builds networks of support, and emphasizes clear, behavior-based plans that can be sustained over time. By blending structure with engagement, SOP strengthens partnerships with families and communities while keeping child safety at the center.