|

|

|

©

2007 Jordan Institute

for Families

Vol.

12, No. 4

August 2007

Juvenile Justice: A Brief Overview

A little more than 100 years ago, we had one system of justice in the United States. We treated children as we would treat adults when they committed a crime. We even put children as young as seven years old to death for their crimes (Taylor, et al., 2002).

In the late 1800’s, children were considered property and often sold by their parents to wealthy businessmen. Children were placed in the workforce or apprenticed at very young ages.

During this period a group of women known as the “child savers” were successful in convincing some key politicians to treat children who committed crimes differently than adults. As a result, in 1899 the juvenile justice system was born. Child labor practices, child abuse, runaways, and other issues facing juveniles were also reviewed during this time.

Changing Attitudes

Just as the child welfare system has experienced different philosophical trends over the years, so has the juvenile justice system. The basic assumption that led to the creation of a separate system of justice was that, compared to an adult, a child is less mature and therefore less capable of intent when committing a crime. Because of their limited capacity for intent, it was believed that children could be rehabilitated more easily. This is often referred to as the traditional model of juvenile justice. Under this model it was believed that the best interests of the child were always paramount and that treatment and rehabilitation could prevent further delinquency.

Around 1960, another way of looking at juvenile offenders emerged and more similarities to the adult criminal justice system were introduced. Children, no longer viewed as property, were seen as having rights and as deserving “due process.” They now had a right to counsel, to notice of charges, to confront and cross-examine witnesses, to remain silent, and to be protected from double jeopardy. Under this due process model of juvenile justice it was believed that the best interests of the child should be sought while providing fundamental fairness and due process.

In the early 1980’s to present day, the model guiding the juvenile justice system changed again. Under the current punitive model the focus is more on the best interests of society rather than on the child’s best interests. The more serious the crime, the more society needs to be protected from the culprit. This is more aligned with the adult criminal justice system. This approach to juvenile justice attempts to prevent future offenses by punishing youth, removing them from society, and holding them accountable.

Types of Offenses

In North Carolina the juvenile justice system is notified of a youth’s delinquent behavior by parents, social

services, or law enforcement.

Delinquency is any behavior prohibited by state juvenile law and includes anything from underage drinking to murder. These offenses fall into two categories: delinquent and status. A delinquent act is anything that would be a crime if committed by an adult. A status offense is an act that would not be considered a crime if committed by an adult, but which is forbidden to children. For example, running away, violating curfew, skipping school (truancy), underage drinking, and smoking are all status offenses. A youth can also be alleged to be undisciplined if he or she is deemed by a judge to be incorrigible or ungovernable.

Juvenile Justice in 2006

According to the NC Department of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention, 29 youth were transferred to adult court in 2006. These youth, if convicted, would be placed in one of the two youth prisons operated by the Department of Corrections. As of 2005, our state had 44 youth serving sentences of life without parole.

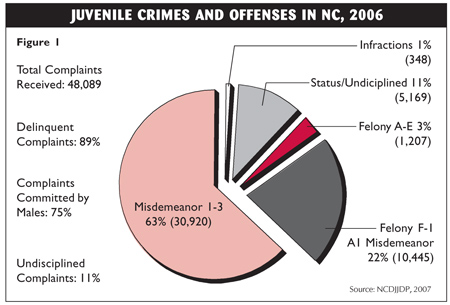

In 2006, North Carolina received 48,089 complaints against juveniles. Eleven percent were for status offenses. The majority of the status offenses were for ungovernable youth, followed by truancy and youth who had run away.

As Figure 1 shows, the remaining 89% of the complaints were considered delinquent complaints (misdemeanors 63%, felonies 25%, infractions 1%). Seventy-five percent were committed by males; 41% were committed by White youth and 50% were committed by African-American youth.

Although most of these cases were processed by the juvenile court system, some were handled by Family Courts. Characterized by a less adversarial approach to justice, Family Court programs currently exist in 11 districts (including 18 counties) in North Carolina. To learn more about them and how they serve families and children connected with child welfare, click here.

|

|---|