|

|

|

Vol.

19, No. 3

July 2014

Identifying Attachment Problems

Understanding the quality of a child's attachment with his caregivers can help you intervene more effectively to promote safety, well-being, and permanence.

Every Child Has Attachment

Before we go further, it's important to understand one fundamental concept about attachment. The question isn't whether or not children are attached to their caregivers. Attachment isn't something a child has or doesn't have.

Attachment develops even in the face of maltreatment and severe punishment. It is the quality of the attachment relationship that is compromised in these circumstances, not the presence or strength of attachment (Carlson, et al., 2003).

In other words, no matter how harmful a child's parents might seem, the child still has a strong attachment to them that needs to be respected. A child removed from an abusive or neglectful home will experience just as much pain and trauma, and possibly even more, than a child separated from a healthy and loving parent. As you probably know from experience, children are unlikely to be relieved or grateful at being "rescued," regardless of how clear-cut the danger may appear to us. In fact, for children who lack a safe and secure attachment figure in their lives, being removed from their home is likely to reinforce their negative beliefs about themselves and the world around them.

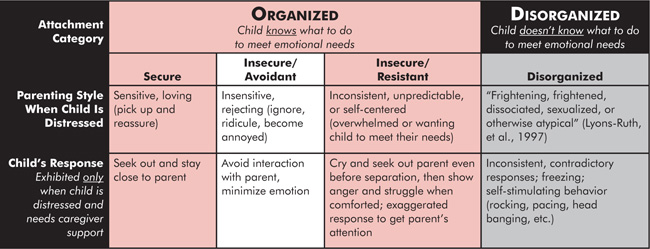

The table below provides detail on the different categories of attachment and what you might see in each when a child is in distress. As the table indicates, there are two main categories of attachment--organized and disorganized.

Organized Attachment

When most people hear the words "organized attachment," they usually think of secure attachment. This is natural. Most children have attachment that can be described as secure. The benefits and hallmarks of this type of attachment are described in detail in the preceding article.

Yet some children's attachment can be considered "organized," even though it is not secure. When caregivers are unable or unwilling to respond to a child's basic need for food, comfort, and nurturing, children figure out other ways to get their needs met. In the process they may develop patterns of behavior with their caregiver that elicits what they need despite the lack of consistent, sensitive care. Some of these patterns are considered "organized" because, in a sense, the child knows what to do and does the same things repeatedly.

While to an outsider the behavior looks problematic, it helps the child survive. It is a coping mechanism that makes sense in the context of the child's primary relationship. However, when transferred to other people, these behaviors create barriers and can make others turn away from giving the child what he most needs: safe, consistent care.

There are two types of insecure attachment:

Insecure-Avoidant

- Child explores with minimal interaction or checking in with the caregiver.

- No extra emotion in sharing delight or upset with parent.

- Child doesn't seek interaction or closeness to the caregiver after separation or when distressed, and doesn't respond when caregiver provides it.

- When distressed, child avoids parent and minimizes emotions.

Insecure-Resistant

- Child seems wary of strangers and shows little interest in normal exploration.

- Child often cries or seeks caregiver even before separation. Unable to happily move away.

- Having the caregiver return or attempt to provide comfort doesn't help or reassure. Child alternates between actively seeking contact and struggling/crying/stiffness.

- Child shows anger and anxiety when caregiver attempts to comfort.

- When distressed, child exaggerates resistance and distress to try to get needed attention from inconsistent or unresponsive caregiver.

(Benoit, 2004; Carlson, et al., 2003; Flaherty & Sadler, 2011)

Disorganized Attachment

This is the category that describes children with the most significant attachment problems. It's likely you work with children who have this type of attachment due to their histories of abuse and severe neglect. In a large analysis that looked at over 80 studies, up to 80% of children with a history of parental maltreatment or drug abuse had disorganized attachment. By contrast, only about 15% of children from low-risk families had disorganized attachment (Van Ijzendoorn et al. 1999, cited in Green & Goldwyn 2002).

Disorganized Attachment

- Caregiver's behavior is "frightening, frightened, dissociated, sexualized, or otherwise atypical" (Lyons-Ruth, et al., 1997).

- Child shows apparently undirected, inconsistent, and sometimes contradictory responses to parent (e.g., an infant who kicks, struggles, fails to focus attention on any one person or activity, without any apparent pattern or rhyme or reason).

- Sometimes child shows abnormal behavior (freezing, repetitive self-stimulating behaviors).

- Child's behavior believed to result from caregiver being a source of fear; child is in conflict between wanting to flee to and flee from the caregiver.

(Benoit, 2004; Carlson, et al., 2003; Flaherty & Sadler, 2011)

These children exist in a chronic, low-level state of arousal and stress: in survival mode. If you have learned that people who try to care for you are dangerous or untrustworthy, then even a caring and well-meaning foster parent who tries to offer comfort could be perceived as a threat.

Children with attachment insecurity, especially disorganized attachment, are at increased risk for oppositional defiant disorder (ODD) and related behavioral disorders, as well as dissociative disorders, and are more likely to have academic and social deficits (Boris, et al., 2007).

What About RAD? |

| Is Reactive Attachment Disorder a form of disorganized attachment? In contrast, RAD is a very rare disorder that results from non-attachment. With RAD, it is the child's lack of a caregiver to attach to that causes the problem. According to Gleason and colleagues (2011), RAD also likely has a genetic component. To learn more about RAD, click here. |

If You Suspect Attachment Problems

The next article offers suggestions for what to do if you suspect a family you are working with is struggling with insecure or disorganized attachment.

Before you turn the page, it may be helpful to note that not all children will continue to have severe attachment problems throughout their lives. In one of the few long-term studies that has been done, 25% of children who were attachment disorganized as infants did not show disorganized attachment at age seven (Lyons-Ruth et al. 1997, cited in Green & Goldwyn, 2002).